One afternoon in February, Catherine Jones was browsing Zintellect, a job board for students seeking science-based internship opportunities in government and the private sector, when she saw an opportunity she couldn’t pass up.

She was reading a listing for the University of Tennessee–Oak Ridge Innovation Institute’s (UT-ORII) Student Mentoring and Research Training (SMaRT) program that would give her a chance to gain research experience in a national lab less than a five-hour drive away. She took her shot just like more than 300 undergraduates who submitted applications. She got it.

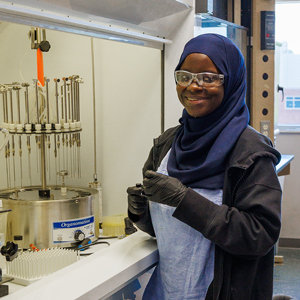

Arriving in Knoxville in June alongside 39 other undergraduates representing 28 universities across the United States, Jones was assigned to a project led by two UT Institute of Agriculture faculty members, Amanda May (Knoxville ’13), a research assistant professor with the Center for Renewable Carbon, and Jennifer DeBruyn, environmental microbiology professor. They spent the next 10 weeks looking at perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances—known as “forever chemicals”—and microplastics to learn about their contaminating effects on plants.

Jones, a senior environmental health science major at the University of Georgia, had lab experience, though it was confined mostly to assisting a Ph.D. student or cleaning up. From her first week at SMaRT, she read academic papers to understand the deeper science behind the methods, and then she conducted experiments under the watchful eyes of her mentors.

“From the beginning, the faculty made it clear that this was a simulation for graduate school,” Jones says. “They entrusted us with reading and interpreting the papers and using what we learned in the lab. We were made responsible for our own learning.”

That level of hands-on exposure, coupled with the unique opportunity offered by UT-ORII—a strategic partnership between a top research university and a federally funded laboratory in Oak Ridge—prompted the creation of the SMaRT program in 2020.

“Students apply based on their area of interest but understand they will be expected to collaborate with multiple faculty beyond a single lab. This is how science comes together across disciplines to solve national problems.”

—Shawn Campagna

Led by Shawn Campagna, who serves as the UT-ORII director of scientific programs and is a UT Knoxville professor of chemistry, the institute houses the Science Alliance, a Tennessee Center of Excellence formalized in 1984 to expand cooperative research with ORNL and improve science and engineering education at UT Knoxville. SMaRT, which has welcomed more than 200 students from schools ranging from Ivy League universities to smaller colleges and universities across Tennessee, ensures the alliance’s portfolio would span the research ecosystem, from undergraduates and graduate students to distinguished scientists.

“This is a critical way for us to expose students to academic and federal research, while providing them with professional development, mentorship and opportunities to present in front of peers and leaders in their fields,” Campagna says. “For most, it is their first opportunity to do research at this scale. These are big projects they’ve undertaken. They’re out there doing real science.”

Running the program is no small feat. Campagna has three graduate research assistants who work year-round to organize the program’s many facets. He is closely supported by UT Knoxville’s Center for Advanced Materials and Manufacturing and Graduate School. In five years, he has recruited scientists from across the UT System and Oak Ridge—they include physicist Ivan Popov, wood chemist Mi Li, biosystems engineer Eminé Fidan and materials scientist Katharine Page—who serve as principal investigators, working with a team of doctoral student mentors to lead cohorts of undergraduates.

“We cultivate our projects before the program starts,” Campagna says. “Students apply based on their area of interest but understand they will be expected to collaborate with multiple faculty beyond a single lab. This is how science comes together across disciplines to solve national problems.”

This year’s students ranged from sophomores to seniors in biology, chemistry, computer science, engineering, math and physics at universities including the University of California, Berkeley; University of Texas at Austin; Mississippi State University and Duke University. They lived together at Vol Hall on the UT Knoxville campus and traveled between labs to conduct experiments, toured facilities, met with scientists and enjoyed social time that included a trivia night at Neyland Stadium and a minor-league baseball game at the Tennessee Smokies stadium.

“This program is so important for undergrads to see the world of opportunity out there for them,” says Adam Imel (Knoxville ’15), a UT-ORII research assistant professor. Imel, a polymer chemist who’s been involved since SMaRT’s inception, participated in a similar summer research program as an undergrad.

Click to Expand Images

“This kind of hands-on experience is enlightening because, no matter what, you’re going to walk away learning something,” he says. “It may be about the research you want and don’t want to pursue, the expectations you’ll have working in a lab environment, or even how to manage the vast personalities you’ll come across in science.”

Many former SMaRT students venture to UT Knoxville to continue their studies after graduation. Rob Patterson, who took part in the inaugural program while at Virginia Tech, participated in an advanced manufacturing project that included students in math, chemistry and political science. They modified surface textures on 3-D printing parts to see if it affected the materials’ strength.

We see the effect it has on their understanding and ability to do research. Even if they realize they may not want to pursue a Ph.D. in the long term, that’s a win because it gives them a better idea of what they want to do with their careers. We want to be good role models and help young people understand their true potential.“But it wasn’t necessarily the project that made the internship worthwhile,” says Patterson, who now is pursuing a doctorate in mechanical engineering at UTK. “It was the connections I made, the exposure to what is, from a manufacturing perspective, one of the premier universities in the country for our discipline with extremely smart people and really interesting technology.”

Hannah Lenkowski had a more unusual introduction to the SMaRT program. A first-generation college student from New Jersey whose undergraduate lab experience was affected by COVID-19 shutdowns, she applied to SMaRT after being accepted to UTK’s doctoral program in chemical and biomolecular engineering. “I knew I wanted to pursue research and wanted to get a head start and some practice before starting classes,” she says.

Lenkowski spent her 2023 internship working with Ivis Chaple Gore, a nuclear engineering professor. The placement was unexpected, considering her interest in immunology. But it exposed her to science she had never seen before.

“It was almost like the SMaRT program intentionally places you outside of your comfort zone to show you there are overlaps you couldn’t see before,” she says. “We had biologists doing computer science, mechanical engineers learning cell culture. That first week together, we were all freaking out, like, ‘We can’t believe they did this to us.’ Then, by the end, we thought it was the best thing ever.”

“We see the effect it has on their understanding and ability to do research. Even if they realize they may not want to pursue a Ph.D. in the long term, that’s a win because it gives them a better idea of what they want to do with their careers. We want to be good role models and help young people understand their true potential.”

—Amanda May

The personal manner of the program and investment from both its staff and faculty are evident across the board.

Michael Qi, who majored in bioengineering at UC Berkeley, interned in 2024, working with Lu Wang, a UT Institute of Agriculture School of Natural Resources assistant professor, on a plant-based alternative to synthetic fibers. Their aim was to strengthen plant fibers to eliminate reliance on plastics. Qi knew there was more work to do, so he applied and was accepted for a second summer, working with Wang and doctoral student Kehao Ren.

“Last year was my first time working in a real lab,” Qi says. “My mentor (Ren) had me running experiments by myself. I used the same techniques and machinery that Ph.D. scientists are using. By the time I got back to college, I had these upper-division classes where they were teaching what I had already learned during my internship.”

May, one of the faculty members with the longest association with the SMaRT program, oversaw a cohort of 12 interns, including Jones, this summer.

“As you’ll see with a lot of the faculty in this program, we’ve been involved for so long because we have a great time working with the students,” says May, who is in the second year of a joint project on the environmental impact of contaminants with DeBruyn. “We see the effect it has on their understanding and ability to do research. Even if they realize they may not want to pursue a Ph.D. in the long term, that’s a win because it gives them a better idea of what they want to do with their careers. We want to be good role models and help young people understand their true potential.”

For the past two summers, May’s funded research on the environmental impact of contaminants with DeBruyn has done just that. Jones, who returned to Georgia more sure about what she could accomplish in the field, wrote letters to May and doctoral student Nimat Ajide-Bamigboye thanking them for teaching her more about her chosen field and for instructing her on how to manage workplace dynamics, work across disciplines and present with confidence.

“The most important lesson I learned is collaboration,” Jones says. “We can’t do this alone.”