By Sarah Joyner | Photos by Angela Foster

DeAnna Beasley’s career in ecology didn’t start until she was a few months away from her college graduation at Wofford College in South Carolina. “I had plans, like most people who go into the sciences, of going to medical school and becoming a doctor,” she says. “Over the years of my college experience, that didn’t feel right to me, but I also didn’t know what options were available to me.”

Something clicked when she took an elective course in ecology.

“I thought it was incredible, this opportunity to think about the environment and its impact on organisms and how organisms are interacting with that space. It was very satisfying for me to think about those concepts.”

But, throughout graduate school and while attending conferences, she felt alone and isolated as a Black woman.

“Throughout my graduate studies and post-doc training, I didn’t see too many ecologists who look like me,” Beasley says. “It is just mentally exhausting to be the only one in the room all the time.”

Those feelings shifted when she joined an information session for the Black Ecologists Section (BES) at an Ecological Society of America conference. BES is an international association providing academic, social and cultural support for individuals of ethnicities and nationalities underrepresented in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields.

“It became this place of home within the conference,” Beasley says. “I felt like I had a purpose.

“In addition to presenting my work, I was working with this group to help increase our presence and hope that the students following behind us don’t feel so isolated and alone when they come to these events.”

Now, as a UT Chattanooga assistant professor in biology, geology and environmental science, she wants to change the view of the conference room for her students.

Fewer than 1 percent of American ecologists identify as Black. Add in American ecologists who identify as Native American and Hispanic, and still only 9 percent of the country’s ecologists are accounted for, according to a study by the Ecological Society of America.

Beasley coauthored an article recently published in the Ecological Society of America Bulletin. Titled “Human Dimensions: Raising Black Excellence by Elevating Black Ecologists Through Collaboration, Celebration, and Promotion,” the article describes those efforts and the why.

The article’s seven authors agree that, to increase the diversity of ecologists, students of color in science need support and mentors who can identify with their specific experiences.

Beasley thinks many Black students are unaware of ecology.

“A number of studies have shown that (Black) students don’t feel comfortable in the outdoors. They don’t see that exposure, and because of the lack of diversity in ecology, they don’t see themselves being represented in that field.”

Beasley provides students opportunities in her own Integrative Ecology Lab, which explores the relationship of insects and their urban environments.

“I try to engage with students who work in the lab and get experience in the field,” she says. “My goal is to create a space where they can at least come away from the experience saying, ‘I could see myself doing this.’ That is my role as a mentor—to kind of show them that there is a space for you. The discipline needs you, needs your perspective, needs your insight.”

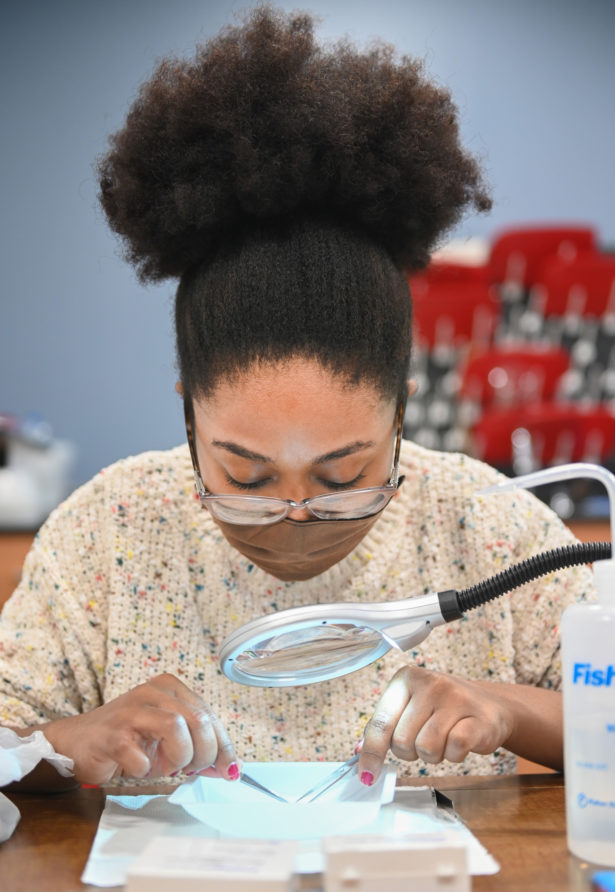

Senior and UTC Honors College student Evann Bailey is working with Beasley this year in the lab for a research experience.

As an integrated studies major, Bailey is concentrating in two felds: biology and entrepreneurship. With a customized degree, she plans on attending medical school and opening her own private practice as an obstetrician-gynecologist someday.

She was drawn to Beasley’s lab research studying the morphology—or physical form—of urban bee wings and whether warmer temperatures are affecting the insects.

“I didn’t even know that, studying their wings, that they could be an indicator of stress,” Bailey says.

Bailey learned about ecology when she came to UTC.

“I didn’t really know much about ecology before I came to college because, at least at the high school I went to, environmental science and ecology just weren’t promoted. They were elective classes, and nobody really talked about it.”

Instead, she was introduced to the science through friends who were participating in their own ecology research, and it grabbed her attention.

As far as diversity among ecologists is concerned, Bailey agrees with her mentor: There’s not enough promotion of ecology to young, budding scientists.

“I definitely think that if there was more outreach early on—maybe as early as middle school and definitely high school—that would bring attention to this field as an option you can go to besides the three standards of chemistry, biology and physics,” she says.