The UT Institute of Agriculture’s Tree Improvement Program (TIP) had been around for a quarter century when, on Jan. 1, 1984, forestry professor Scott Schlarbaum showed up for his first day on the job. The new director’s mission was clear: continue and expand on the work of his predecessor to improve the health and productivity of Tennessee forests. One way he’d do this is by establishing and maintaining orchards to provide seed for reforestation.

Naturally, that’s the first idea that came to mind when, in the winter of 1998, two men from Jack Daniel Distillery—then general manager Tommy Beam and production manager Doug Clark—reached out to the TIP concerned about the abundance of sugar maples in their area. The distillery relies heavily on this tree species, burning it to make the charcoal used to mellow its whiskey. An inventory analysis undertaken by a colleague of Schlarbaum’s showed no immediate cause for concern. But Beam and Clark wanted to do something anyway.

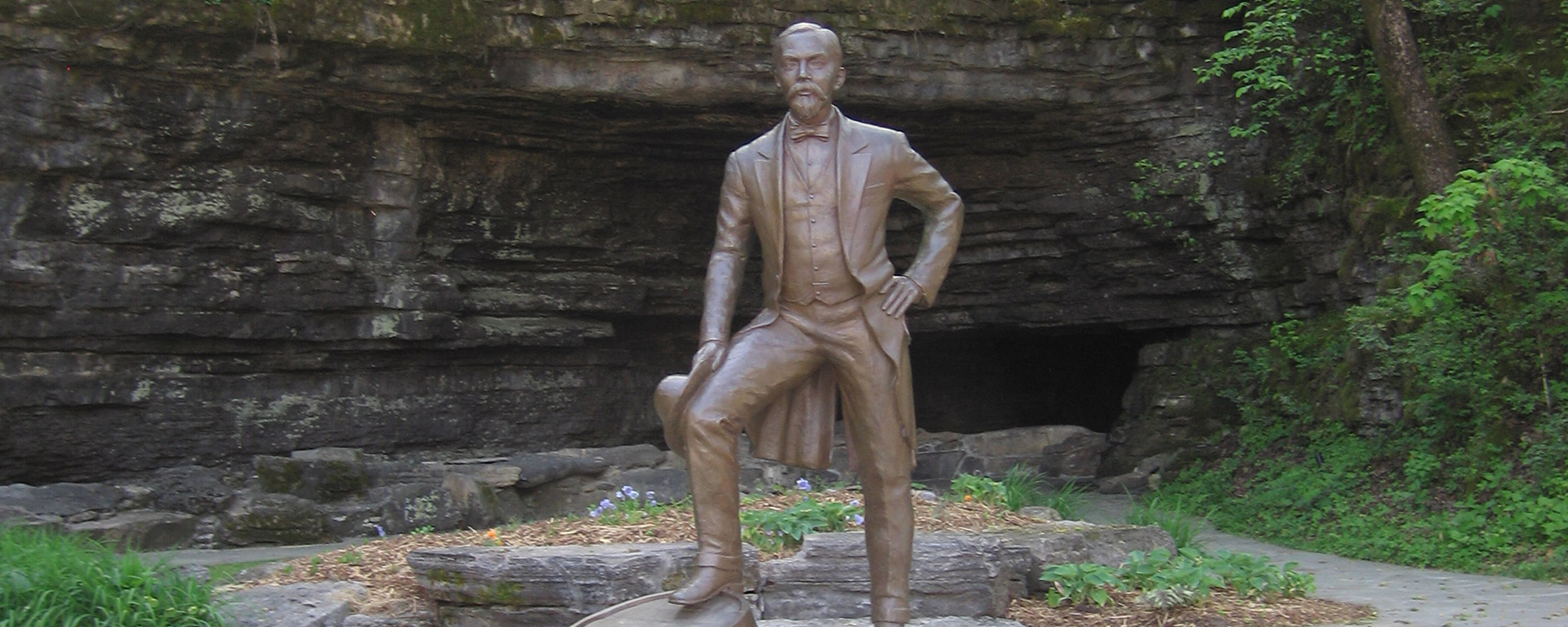

So, on a spring morning in 1998, just north of Lynchburg, they stood watching Schlarbaum survey more than two dozen acres of unblemished pasture that belonged to the oldest and most famous whiskey maker in America. Schlarbaum took note of the land and its geography. It was a place calling out for legacy—an opportunity for Jack Daniel’s and the university to do something that had never been done before.

“So we made a deal,” Schlarbaum says.

The distillery would bring in the professor and a small UT-based crew to oversee the planting of a sugar-maple genetic test on a 27.5-acre section of land it owned. The test would later be converted to an orchard, which would produce seeds to grow into seedlings for reforestation. If Jack Daniel’s or its parent company, Brown-Forman Corporation, needed access to sugar maple wood in 50, 100 or 200 years, they would have it. But why stop at one species?

Jack Daniel’s iconic whiskey also relies heavily on white oaks, which it uses to form its barrels (roughly 20,000 of which sit, at this moment, in barrelhouses scattered throughout the hills and valleys of Lynchburg). There was also room for orchards of other species: black walnut, butternut and a variety of oak species. It would be a bounty of trees on distillery land.

The story could read like a fairytale. But Schlarbaum is a scientist; he does not get sentimental over his work. And he does not make short-term commitments or work with hesitating benefactors.

“You’ve got to understand you’re committing to something that will be around for decades,” he said, as straight as he could to the distillery’s leaders. Beam and Clark extended their hands. And on that handshake agreement was built a partnership between Jack Daniel’s and UT’s TIP that, 25 years later, serves as one of the finest examples of collaboration between a corporation and public institution for conservation and sustainability in Tennessee.

Since 1998, 3,100 trees and grafts have been planted, grown and cared for, transforming what was once barren Middle Tennessee pastures into a young forest. The initial orchards were such a success that the distillery made available an additional 38 acres to Schlarbaum and his team. This land is presently being filled with orchards of different species. Company leaders estimate that, in the past 20 years, they’ve directed $550,000 worth of funding to the orchards between labor, equipment and research budget.

“What Scott does is so thoughtful and organized,” says General Manager Melvin Keebler, who oversees Jack Daniel’s operations in Lynchburg and has been involved with the partnership in different capacities for a decade. “One presentation, he walked us all the way back to Rome: the ways the trees were used, a brief history of all hardwood species.

“He goes through such detail in explaining and educating us. That type of knowledge transfer was important for us to understand the kind of impact we were having. It’s bigger than Jack Daniel’s. It’s about the whole sustainability effort.”

Since Jack Daniel’s and the TIP began collaborating, many of Tennessee’s foresters, including those in key leadership positions in state and federal agencies and recognized as the field’s established experts, trained under Schlarbaum in Lynchburg orchards.

“I cruised the land and helped in the lab,” says Jaxon Maxedon (Martin ’97, Knoxville ’00), who earned a bachelor’s in wildlife biology from UT Martin and a master’s in forestry at UTIA. While finishing his undergraduate degree, a mentor connected Maxedon, now the executive director of the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA), to Schlarbaum, who took him under his wing, exposing him to mixed mast species planting projects with Jack Daniel’s, TWRA and the National Wild Turkey Federation. After graduate school, Maxedon worked as a wetlands forester in West Tennessee, planting 10,000 acres of trees on TWRA properties and collaborating closely with Schlarbaum on research along the way.

Over the years, Maxedon has seen the impact of the TIP’s mission at work across the state. “It’s very important that we get these local seed sources into the landscape and not have to outsource that to another state,” says Maxedon, who serves as an advisory board member for the newly established School of Natural Resources (formerly the Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries).

But it’s not as simple or easy as it sounds. The demand outweighs the supply. With increased pressure on natural resources and a changing climate, natural forests must be supplemented by locally adapted and, in some cases, genetically improved seedlings grown from the seeds produced by orchards like the ones Schlarbaum and his team establish.

“There is always a shortage of white oak in the state nurseries,” says Stacy Clark (Knoxville ’96, ’99), a research forester with the U.S. Department of Agriculture and a leading figure in the planting and study of oak species.

While completing her master’s degree in forestry under Schlarbaum, Clark collected the seeds used to establish sugar maple and white oak on Jack Daniel’s property.

“What happens is that nurseries will go out and find sources anywhere they can. Sometimes they’re buying seed from one or two trees. But, what if one tree is bad or susceptible to disease? You don’t want low genetic diversity. That’s why seed orchards are so important,” she says. “But who’s going to take 30 years, spend all this money to put in an orchard, keep it maintained, monitor and measure it? It takes a lot of resources.”

The TIP operates other large-scale orchards at the Ames AgResearch and Education Center in West Tennessee, TVA’s Norris Reservation, Cherokee National Forest (the largest oak orchard in the U.S.) and other locations. Only in the case of Jack Daniel’s does it work so closely with a corporate partner.

Keebler acknowledges how improbable it seems on the surface that a business—more so, a whiskey distillery—would invest so much money and time in an orchard from which it may never see a return. The first sign of reproductive maturity in the sugar maples on the property was only evident in 2017.

“The orchard is nowhere near commercial seed production,” Schlarbaum says. “So, 25 years of investment and no return yet.” The white oaks produced a commercial-sized crop for the first time in 2021.

However, Jack Daniel’s remains fully bought in. The orchards are the longest running of the distillery’s sustainability initiatives, which include upcycling sugar maple charcoal for use in barbecues and repurposing used barrels for furniture and for use by other liquor makers.

“Internally, it’s one of the things we are most proud of,” Keebler says. “Twenty-five years ago, Scott got operations people in Lynchburg so passionate about it they actually volunteer to go out and be part of the work. It doesn’t matter if it’s our executive leadership team, board of directors, family shareholders—when they come to Lynchburg, they always ask to go out and see the tree orchards.”

Outside of the business, the arrangement has proven fruitful in other meaningful ways. Ami Sharp (Knoxville ’01), a research associate who’s been involved with the Jack Daniel’s seed orchards since graduating with her bachelor’s two decades ago, has worked alongside Clark, who’s worked alongside Maxedon.

She spends more than a month on the road each year planting, collecting seeds and evaluating tree health. In early February, she planted a hickory orchard at UT Southern. Last time she visited Lynchburg, she brought Rachel Brock, an undergraduate forestry major.

“It’s a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for me to have this kind of experience and to have people like Dr. Schlarbaum and Ami helping me maneuver through my career,” says Brock, who in January helped with baldcypress and water-oak plantings. “It’s like I have a wild card in Uno or a really good hand in poker.”

Now 71, Schlarbaum no longer picks up many acorns himself. And he tries not to get sentimental about what he’s accomplished in his career, the foresters and conservationists he’s trained, and the orchards he’s established. He is, after all, a scientist. But when lying in his bed at home, struggling to fall asleep, he likes to picture the white oaks at Jack Daniel’s. He’s lying in the orchard’s understory, looking up as the wind blows through the leaves. He closes his eyes.

“It’s a very enjoyable and calming experience,” Schlarbaum says.

To learn more about UT’s Tree Improvement Program, visit its website at treeimprovement.tennessee.edu or follow on Facebook (TENNTIP), Instagram (tenntip) and YouTube (@uttip).