Featured image: Daniel Wiggins, Shawn Butler and Austin Scott and Butler’s patented design.

By Sarah Knapp

“There’s got to be a better way to do this,” Shawn Butler muttered to himself as he hand sprayed cover crops with herbicides to prepare the field for cotton planting.

Butler (Martin ’14, Knoxville ’16, ’19) knew there had to be a more efficient way to terminate strips of living-cover crop than the single-nozzle boom sprayer he was given. Butler, then an employee of the West Tennessee AgResearch and Education Center, worked on a trial herbicide experiment in 2013 that was designed to destroy cover crops planted between cash-crop seasons for weed suppression, and when the first round of trial herbicides proved ineffective, he was left to respray hundreds of rows of cover crop, each 300 feet in length, by hand in the middle of February’s 35-degree temperatures.

Cover crops help maintain healthy soil during the offseason by keeping the soil saturated and locked with nutrients. When terminated, cover crops act as an organic mulch to suppress weeds and reduce herbicide usage, but the process of terminating those cover crops can be difficult, as Butler learned spraying the fields.

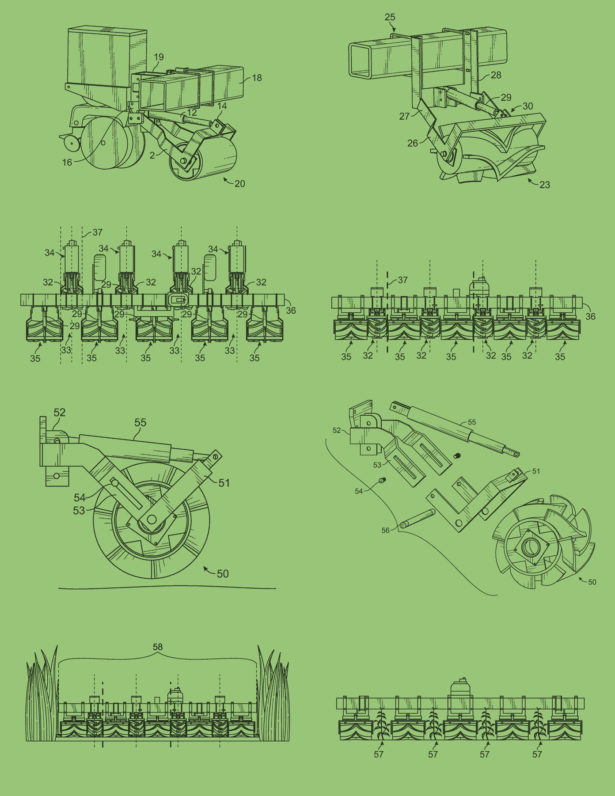

After finishing spraying the fields, Butler started researching ways people managed cover crops in the past and came across the roller crimper. The solid metal steel cylinder with blades fixed around the cylinder allows the machine to pinch the plants stems when making contact with the ground, cutting off the flow of water and nutrients. But the solid cylinder alone just temporarily lays the plants down and is not able to adapt to the changes in terrain.

Butler thought it would work better if he adapted it.

“Why don’t I just take this roller-crimper, slice it into a bunch of sections, and then I can roller crimp this cover crop in these strips instead of a spray killing it?”

The idea stayed just that until a class at UT Martin in 2014 changed everything.

Butler, along with his friends Austin Scott (Martin ’14) and Daniel Wiggins (Martin ’15), were students in Paula Gale’s soil and water conservation course when Gale gave her students the option of taking a final or competing in the College of Agriculture and Applied Sciences entrepreneurial pitch competition for an A. Butler described his idea to his friends, and the trio formed a business model to present in place of studying.

Butler’s flex roller-crimper is designed as individual drums, allowing each crimper to pivot and meet the ground individually, ultimately killing the cover crop, no matter the terrain, in a time- and cost-efficient manner.

“You need some type of unit that is more flexible… and there just hasn’t been a lot of good options out there,” Butler says. “It would be a tremendous honor in itself to develop a product that solves a problem with adoption of a sustainable practice.”

When the students first presented at the ag innovation competition, Gale says they did a good job.

“I had looked at the competition as an opportunity to give them some public speaking experience and some teamwork experience, and they got both of those and more,” she says. “They learned more than anything I could have taught them. You have to learn by doing.”

They won UT Martin’s ag innovation contest but also continued to compete in regional and national competitions, winning enough prize money to begin a formal business called FarmSpec, or Farm Specific Technology. From competing in UT System contests like the Boyd Venture Challenge, sponsored by UT President Randy Boyd, to national contests such as the Farm Bureau Rural Entrepreneurship Challenge and the Howard Buffett Ag Innovation Contest, FarmSpec began making a name for itself in agriculture.

However, Butler, Wiggins and Scott were each pursuing individual careers in agriculture. While Wiggins and Scott still hold equity in the flex roller-crimper, they recognize that it was originally Butler’s creation and allowed him to continue marketing the product as he desired.

“Shawn had the idea, … but I think all of us combined together troubleshot it and made the idea into something,” Wiggins says. “I knew it was a good idea, and I knew there wasn’t anything on the market, but I didn’t think we could have a company and a product that one day (he) will be able to sell… I just think from the standpoint of seeing them in use and knowing that I was a part of that, from an ‘easy A’ contest at UT Martin, would be the coolest thing.”

Butler partnered with the UT Research Foundation to begin the patenting process while still a UT Martin student in 2014 with the hopes of seeing it manufactured to help farmers incorporate organic farming practices in a cost-efficient manner. After graduation, he continued working toward his goal while earning his master’s (’16) and doctoral (’19) degrees in agronomy at the UT Institute of Agriculture Herbert College of Agriculture.

“One of my bucket-list items was always to get a patent,” Butler says. “Initially I was like, ‘If I can just make a dollar off of this, I’ll feel great.’ Literally when I signed the license over to the UT Research Foundation, they sent me a dollar in the mail along with 60 other documents that I had to sign, but I got my dollar bill. I was happy at that point.”

But he still wants more.

“It would mean the world to (manufacture) a physical piece of equipment that helps a grower’s efficiency and profitability,” he says.

Butler, now a cotton development specialist for PhytoGen in Central and Southeast Georgia, received the patent for the flex roller-crimper in October of 2019 and says none of it would have been possible without the UT Martin innovation contest created by Todd Winters and Gale encouraging him to compete. “Without generating a platform for potential entrepreneurs at UT Martin, (FarmSpec) would have never happened. I am very thankful for UT Martin,” Butler says.

While Butler is the patent holder, all three men said it would be special to see the flex roller-crimper in use after all of their hard work.

“It’s good to just see something that you helped build be put to use and see other people gaining something from it,” Scott says.

“It’s just that feeling of accomplishment that I can change something about the industry I work in every day for the better. So, seeing somebody else benefit from an idea that I helped develop would be awesome.”

“I’d be tickled to death to see them in any field in West Tennessee as I drive by,” Wiggins says.

Butler is still considering how to manufacture and distribute or license the flex roller-crimper and best market it to farmers looking for innovative techniques to implement on their farms.

While it may have taken seven years, two partners and three degrees, Butler found a better way.