By Gina Stafford | Photos by Sam Thomas

One of the largest wind tunnels in academia has just begun operating in Tennessee, and if John Schmisseur has his way, it’s going to ignite intellectual and economic fire power across the state.

Schmisseur is a UT Space Institute professor of mechanical, aerospace and biomedical engineering and the H.H. Arnold Chair in Computational Fluid Dynamics. When he left the U.S. Air Force four years ago, he brought a vision to the “blank slate” of opportunity he found at the Space Institute. Firing up a brand-new wind tunnel is only the first phase.

For the last 13 years of a 23-year career in the Air Force Research Lab, Schmisseur ran the hypersonics basic research program, including selecting university proposals for Air Force funding.

“I had the luxury of interfacing with the best and brightest minds in hypersonics and building great relationships with pre-eminent researchers in their fields. That prepared me very well for the next half of my professional life, because now, instead of flying to Caltech and Texas A&M and Minnesota, I get to be here,” Schmisseur says. “I wanted to make a strong contribution in hypersonics, and Tennessee is a great match.”

True to his military roots, Schmisseur named his program—of which the new wind tunnel is a part—with an acronym: HORIZON, for High-Speed Original Research and Innovation Zone. The name also alludes to the military’s first post-World War II technology forecasting report, “Towards New Horizons.” Subsequent Air Force reports also have had “horizon” in their names.

“Knowing this,” Schmisseur says, “we named our research group HORIZON so our stakeholders in the Department of Defense would recognize that and realize we are forward-looking.”

UT HORIZON looks forward with ambition. Schmisseur wants the program to conduct foundational research in aerothermodynamics—the study of how high-velocity gases behave—and in ground-based tests of aerodynamic phenomena. National leadership in aerospace and defense research is the goal.

HORIZON got a boost in 2016 with $1 million in state funds, based on potential dividends to Tennessee’s economy from aerospace innovation and discoveries, to build the Mach 4 wind tunnel now at UTSI.

“Now, we have the big job to demonstrate it will do what we’re saying,” Schmisseur says. “The good news is, we’re already hearing from industry and getting very positive feedback from the community.”

Within the next year, Schmisseur’s hope is that the Space Institute’s experiments will cross the road to Arnold Engineering Development Complex (AEDC). Also known as Arnold Air Force Base, AEDC is just across Wattendorf Memorial Highway from the institute in this remote area of Coffee County. Schmisseur calls AEDC the crown jewel and epicenter of Air Force hypersonics research, operating more than 55 aerodynamic and propulsion wind tunnels, rocket and turbine engine test cells, ballistic ranges, sled tracks, centrifuges and other specialized units.

But AEDC testing takes hundreds of thousands of dollars per week, if not millions per test, Schmisseur says.

“I wondered how we could do something that easily feeds into AEDC, and here we’ve set up TALon right outside the gate.”

TALon—Tennessee Aerothermodynamics Laboratory—is the acronym for the new wind tunnel facility. Schmisseur says it creates “a natural pathway to a discovery, innovation, technology development and early research environment.”

Just how big is one of academia’s largest wind tunnels?

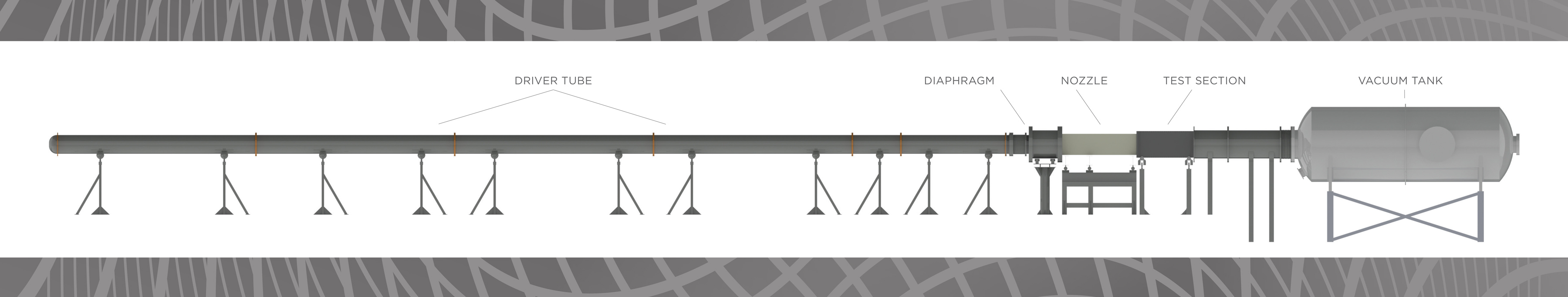

It’s about 24 inches in diameter and 156 feet in length, housed in a nondescript metal building on campus. When the tunnel is operated, air flows due to a powerful vacuum created in a large tank outside the building and attached to the end of the 105-foot tube that passes through an exterior wall.

“Most universities that have an aerospace program have a supersonic wind tunnel, and they’re all about this big,” Schmisseur says, his hands a few inches apart.

TALon is 60 percent of the size of AEDC’s Mach 1.5 to Mach 5.5 facility. The research-scale size complements what’s at AEDC, Schmisseur says. “We can create a representative Mach 4 flow field and in just about 200 milliseconds—2 tenths of a second—of operation, look at the instabilities, the unsteady phenomena that occur in the high-speed flow over a body. The characteristic time scale is on the order of 1 millisecond, so 200 milliseconds is a lifetime for those types of features, and we can measure them very adequately in a short duration using our high-speed diagnostics.”

As a research-scale facility, TALon will offer relatively low-cost experimentation, tens of dollars per test.

Coming next is a Mach 8 facility, thanks to a recent Air Force funding award. This facility will be capable of hypersonic range–velocity of more than five times the speed of sound, or Mach 5. At sea level, that is in excess of 3,800 miles per hour.

“We want to use hypersonic research to drive new accomplishments and growth from an industrial and economic standpoint here at home,” Schmisseur says, “and understanding how test data ultimately translates into the acquisition process would benefit manufacturing.

“Aerospace and defense also are increasingly important in Tennessee—it’s the fourth-largest driver in Tennessee’s economy. UTSI is gearing up to support that with new discoveries and innovative technologies that will ensure aerospace defense flourishes in Tennessee.”

Eventually, plans call for a full-spectrum complex of research facilities ranging from supersonic to hypersonic conditions.

Phil Kreth, research assistant professor with the Space Institute’s HORIZON program, is overseeing design and construction of the TALon complex.

“There are a lot of technical challenges with building a facility at this scale, but for me, it’s also extremely exciting being part of building a new hypersonics program here at the Space Institute,” Kreth says.

HORIZON is already involved in some independent research collaborations—working with a local military firearms manufacturer and with some faculty at Oak Ridge National Laboratory on computational studies.

“This facility—and the program—Kreth says, “will help us answer a lot of questions.”