By Shawn Ryan

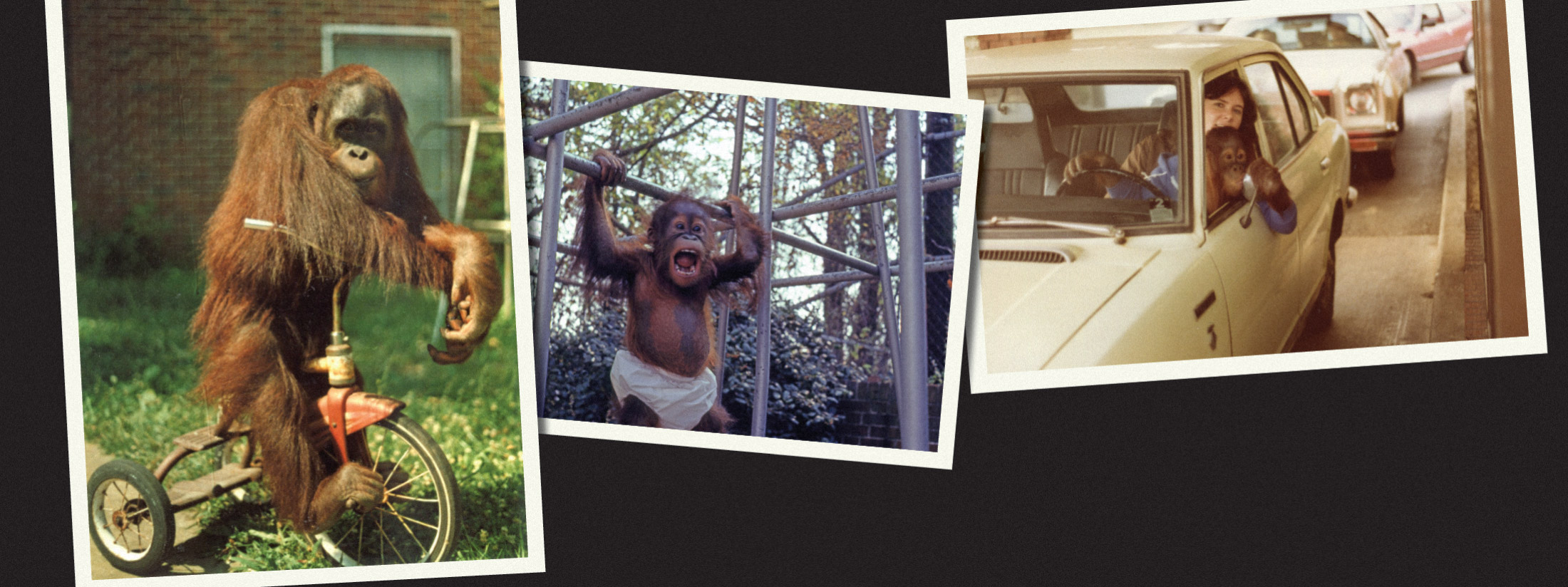

Photos courtesy of Lyn Miles

Back in the 1980s, when police officers at UT Chattanooga prepared for their shifts, they made sure they were equipped with more than the usual handcuffs, pepper spray, batons and weapons.

“Most police departments at the start of their shifts line up and check their guns. Ours did that, too, but they also made sure they had cans of Coca-Cola and some M&Ms in the car,” says Richard Brown, former UTC chief of police, laughing heartily.

The treats weren’t there for the officers.

They were to satisfy the sweet tooth of Chantek the orangutan.

“Our security staff had to learn how to handle him, but he trained them, really,” says Brown, now UTC executive vice chancellor of finance and administration.

Chantek, who died in 2017 at 39, spent about nine years at UTC, where anthropology professor Lyn Miles worked with him, eventually teaching him more than 150 words—the vocabulary of a 2- or 3-year-old child—in American Sign Language for the Deaf. It was the first time someone had tried—and succeeded—to teach an orangutan to sign. In 2014, the project was highlighted in a PBS documentary titled “The Ape that Went to College.”

Having Chantek at UTC was a “remarkable opportunity and privilege,” Miles says. “I mean, we had some challenges, but this is the kind of research that would have been done at a university like a Vanderbilt or a Yale, and we got to do it here at UTC.”

Brown says the research brought national recognition to the university, which at the time was a small Southern school.

More than sign language, though, Chantek—the name means “beautiful” in Malaysian and is usually used for female primates—learned the ins and outs of life on a college campus and a city.

“He knew to cross a street, to look both ways,” Miles says. “When we would get in the car, he would sit in my lap and—this would probably get me arrested—I worked the foot pedals, and he would steer. Like a little kid. And he understood traffic lights. He knew you stop at red and you go at green, and he looked both ways.”

He put metal slugs in soft-drink machines, trying to get a Coke or orange soda. He loved cheeseburgers and called ketchup “tomato toothpaste.”

“He knew a path to his favorite places in Chattanooga,” Miles says. “There was a Dairy Queen on the corner, and he knew how to get there. He knew the way to McDonald’s and the other fast-food places. Local restaurateurs would often allow him—in off hours—to have a meal.”

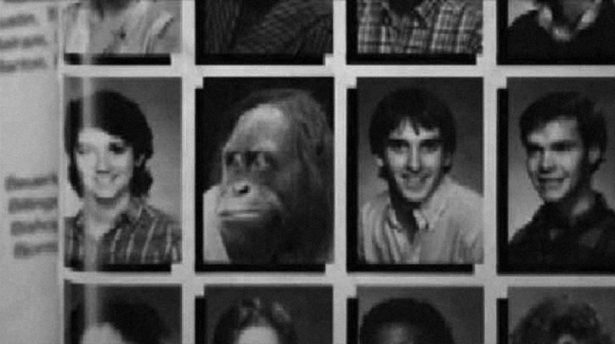

His photo was in the UTC yearbook next to students, and he described other orangutans as “orange dogs.” He’d go to the school’s children’s center to play with the kids, make art and participate in other activities.

“As much as possible, we tried to give him a human childhood because that’s the only way you could test if he could learn language the way we would use it in conversation,” Miles says.

But he also was a rascal. He played tricks on students who were walking with ice cream cones or candy bars, jumping out at them so they’d drop it and he could grab it. When he had to go to the bathroom, they’d take him to the closest in Brock Hall, home to the Department of Anthropology. It was a girls’ bathroom.

“He’d go into his stall and close the door, so he’s locked in there. We couldn’t get to him. He would wait until a young girl would come into the stall next to him and then this hairy, orange arm would come up under the wall and she’d scream and carry on.”

Wherever he lived, however, Chantek was an escape artist. At UTC, his home was in a large grassy area with a trailer where he slept and ate. It was surrounded by a chain link fence. Didn’t matter.

“We did a lot to keep him in, and he kept getting out,” Brown recalls with another laugh. “The cognitive abilities of this animal were so strong. It’s almost hard to call him an animal.”

Maintenance men told Linda Sue Stephens, who has been in UTC Facilities Planning and Management for more than 30 years, that Chantek would get out of his enclosure, wander campus for a while, then go back home to his trailer when he got tired.

When Chantek was transferred to Zoo Atlanta in 1997, keepers there quickly contacted Miles with a problem. She wasn’t surprised at their question.

“They called me in a panic, and they said, ‘He’s disassembling his cage. What’s going on?’ And I said, ‘Well, he knows how to use all these tools,’” she recalls. “What he wanted for his birthday and holidays was a complete workman’s tool belt with a hammer and screwdriver and everything hanging off it.”

Born in Atlanta’s Yerkes Primate Center, Chantek came to UTC when he was 9 months old. For the next eight years, Miles worked with him, becoming a surrogate mother and best friend. She’d hold his hand when they walked around the UTC campus. She’d take him on excursions to Point Park on Lookout Mountain, to Lake Chickamauga where he liked to chase the fish and to local hang-gliding parks where he like to watch the gliders. (No, he never flew with them.)

For Miles, none of it was particularly shocking.

“We know now how incredibly intelligent chimps, gorillas, orangutans and bonobos are. Not only can they learn language like Chantek, but on their own in a natural setting, they have culture. They learn from each other. They have families. They form political alliances. They make and use tools. They’ve developed medicine. They lie and deceive. They have so many of the elements that we would consider to be human culture on a rudimentary level.”

Despite his fun-loving side, Chantek displayed the usual traits of an orangutan, which are different from other primates.

“Mostly you know chimps in a circus or a zoo, and the chimps are noisy, and they’re hopping around, and they’re making noise. They want something, and they’ll find it, and they’ll put it on their heads or they’ll smell it.

“Orangutans are nothing like that. They’re very self-focused, very interior. Chantek would be very quiet. He would look and watch,” Miles explains. “I wouldn’t say ‘introverted’ because he was so curious about the world. But he was kind of introspective. He also was pragmatic and kind of whimsical.”

But, in 1986, he escaped from his enclosure at UTC and reportedly jumped on a female student. He was sent back to the Yerkes Primate Center, and his life was drastically different—he lived in a 5-foot-by-5-foot cage. He grew to 500 pounds, about 200 pounds overweight. Eleven years later, he was transferred to Zoo Atlanta, where he was around other orangutans and eventually found a mate.

Although he was depressed at Yerkes, his personality returned at the zoo, but he always wanted to go back to UTC and live with Miles.

“One of the times he got out of his enclosure at the zoo, I told them, ‘Just give him hamburgers, so he’ll sit.’ And that’s what happened, although they still (tranquilizer) darted him,” she says.

Back in his enclosure, Miles, who was visiting him, signed: “We need a discussion. What did you do?”

“And he just sat there; he knew he was bad. Then he said, ‘But you could get the key and let me out.’”