By Sandra Harbison

Photos by Phil Snow

Growing up, Nathan Chumbler had two passions: a love of animals and a desire to be an Army officer.

“My grandfather was an Army officer; my uncle was an Army officer. I wanted to follow in their footsteps,” Chumbler says. “When I found out I could be both, it was pretty much a done deal.”

An ROTC scholarship helped the Smyrna, Tennessee, native pay for his undergraduate degree at Tennessee Tech. After graduation, he was commissioned as a second lieutenant before being granted an educational delay to attend the veterinary college at UT.

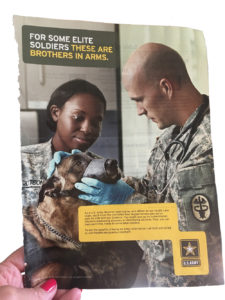

When he earned his doctor of veterinary medicine in 2010, Chumbler was promoted to captain and joined the ranks of the Army Veterinary Corps, one of the six corps of medical specialists in the U.S. Army Medical Department. He served with the 463rd Medical Detachment (Veterinary Services) in Fort Benning, Georgia.

“When I graduated from veterinary college, I had no idea what kind of veterinarian I wanted to be. I loved so many aspects of it,” Chumbler, currently an emergency and critical care resident at the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine, says. “Then I started working with military working dogs and realized that’s my calling.”

A few months following graduation, the 463rd deployed to Afghanistan to join Operation Enduring Freedom; it was the first of three separate assignments for Chumbler. In Afghanistan, Chumbler provided medical care for military working dogs as well as food safety and support.

“As a veterinarian in the Army, your job isn’t just about animals; it’s also looking after people’s well-being from the food they buy,” he says. “The food protection mission with the Army has expanded over time, and the Veterinary Corps has been the executive office over it.”

He describes his next mission as the exact opposite of Afghanistan—three years in Hawaii where he ran a veterinary clinic taking care of military work dogs as well as pets owned by those living on the base. Again, protecting public health was a key role for the veterinarians.

“We inspected the goods purchased and ensured they are being stored properly,” he says.

Following Hawaii, Chumbler deployed to Kuwait as chief of veterinary services. “At that time, there were operations being conducted in five countries in the Middle East, and we were the stepping-off point for distribution in those countries,” he says.

But the military working dogs he had first encountered in Afghanistan kept pulling at his heart. The majority are German shepherds and Belgian Malinois, breeds known to be very smart, loyal and athletic.

“I saw a lot of trauma, a lot of actual combat-related injuries and realized that I wanted to be able to feel very comfortable in my response to those injuries but also in advising others,” he says.

Now, under the guidance of board-certified emergency and critical care specialists in the intensive care unit at the UT John and Ann Tickle Small Animal Hospital, Chumbler deals with life-threatening emergencies and manages critically ill patients. On any given day, the ICU caseload runs the gamut: animals hit by a car, heatstroke, dog bite wounds, recovery from neurosurgery.

He’s experiencing a caseload he can pull from when he goes back on active duty. Chumbler, who was promoted to major in 2016, will return to active duty when he completes his residency.

Even before pursuing his residency, Chumbler had started a two-day program in Hawaii for dog handlers to learn about assessing and triaging various combat-related injuries, since the handlers are the boots on the ground and the first responders in battle. He has also worked with human medics to help them feel more comfortable helping an injured dog.

“What I realized in Afghanistan is I would like to try to make an impact by training others on how they can properly assess injuries and what they can do prior to getting them to a veterinarian,” he says.

When he first entered the Veterinary Corps, Chumbler witnessed firsthand the bond between a military working dog and his or her handler, which is different from that between an owner and a pet. The Army uses the term “force multiplier” when describing military working dogs; the dogs truly save lives and have an impact on the battlefield. That can make hard decisions even harder.

“It’s tough and gut-wrenching to see the trauma and injuries, but as a veterinarian, the most difficult thing to go through is euthanasia. When you talk to a handler and they can tell you how this dog saved their life, it’s a little different. Seeing that loss is one of the hardest things I experience. I will never get used to it.”