By Gary Hengstler

It’s a familiar scene in TV and film: The doctor in the operating room applying CPR and a colleague calling out, “We’ve got a pulse!”

Certainly not as dramatic, but for Mark Schorr, perhaps there was some semblance of that satisfaction when he got the results of his multiyear work to examine the mitigation of Citico Creek, a severely degraded stream in Chattanooga that flows into the Tennessee River near a water purification plant.

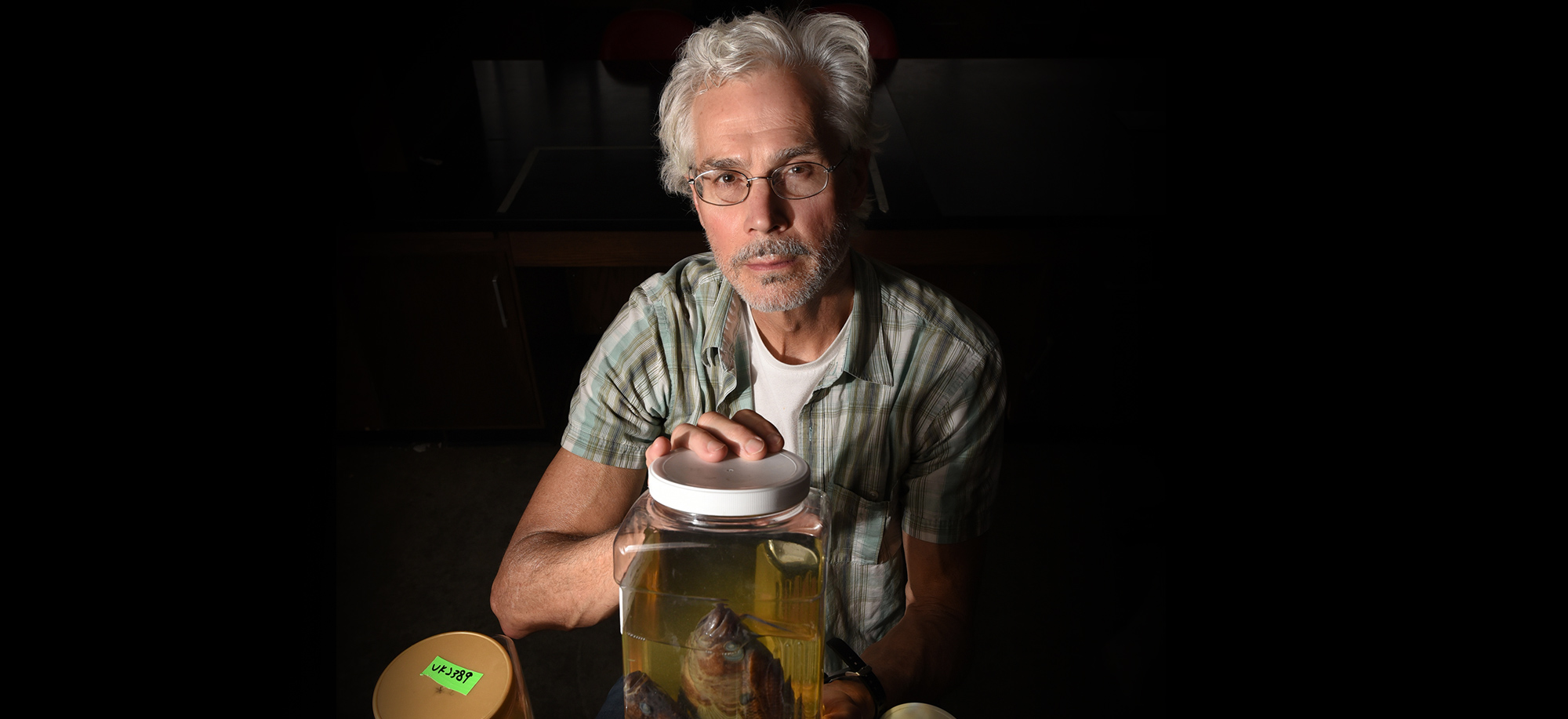

Schorr, a professor of biology at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga (UTC), researches stream fish ecology, with an emphasis on water pollution issues and population/community ecology. Graduate and undergraduate students working in his lab have conducted research to address the following problems:

- influence of coal mine drainage on stream water chemistry, habitat, and aquatic life in the Cumberland Plateau;

- watershed-stream relationships that involve urban/agricultural land use;

- localized effects of road culverts on stream habitat;

- historical and contemporary patterns in the distribution and abundance of sunfish in reservoirs in the Tennessee River drainage.

Water quality assessments comprise an important component in many of Schorr’s studies. Schorr cautions that water quality—a complex term—refers to selected characteristics of water, in which data are compared to standards for protecting human health and aquatic life.

Schorr and his students have documented effects of human disturbances on stream water quality at more than 100 sites in the Chattanooga area. In his research, water quality assessments focus on the ecological health of streams. In addition to analyzing data on stream-water chemistry (temperature, oxygen, pH, etc.) and habitat features (flow, depth, channel substrate), macroinvertebrate and fish data are used identify the ecological health of creeks and watersheds. All of his study streams are tributaries to the Tennessee River.

From 1998 to 2000, Schorr was retained by the city to collect and analyze baseline data on watershed urban land use, water chemistry, habitat and aquatic macrofauna in Chattanooga-area streams. Currently, he is measuring the effects of the city’s mitigation efforts to undo decades of damage to polluted streams in Chattanooga’s urbanized watersheds. One such stream is Citico Creek, which has more than 90 percent urban development in parts of its watershed. “It has a slew of pollution issues that affect not only the ecology of stream but also the people that live in this area,” he says. “Many sections of the stream are posted, warning people not to come in contact with the water because of high bacteria levels.”

Like many urban streams, much of the Citico Creek system had been straightened and lined with concrete to prevent flooding in that area.

However, shooting the water quickly through the stream, he says, “is a huge insult to the stream and involves an extreme degradation. Moreover, it just pushes the flooding down to somewhere else.”

Such was the case with Citico Creek.

Pre-mitigation data collected at the Citico Creek study site indicated that more than 60 percent of the streambed was concrete. Post-mitigation data showed that 98 percent of the streambed was composed of boulders, cobbles or gravel. In addition to removing the concrete and mortar from the channel, the city installed a series of rock wiers that increased pool habitat, which increased water depth and reduced current velocity. These habitat improvements allowed more fish species – species that should have been there normally – to occupy this part of the creek.

When he and his team of UTC graduate students started, they consistently found one species, the Western Mosquitofish, which Schorr describes as “a very hardy species that can handle low oxygen levels and a lot of pollution.”

After the mitigation in 2008 and 2009, Schorr and his students found two species of minnows and five species of sunfish, including the largemouth bass. (Family Centrarchidae, including Largemouth Bass Micropterus salmoides).

Essentially, using fish assemblage data and the “Index of Biotic Integrity (IBI), which rates a stream’s health,” the Citico Creek site went from “very poor” to “poor.”

There was a pulse.

“In terms of its biotic health,” Schorr says, “it is approaching what we see in other urban streams in the area. Before that, it was so severely degraded that it had the worst IBI rating you could get.”

While many still cling to the notion that nature and streams will continue to be self-cleaning, Schorr poses the stark reality: “I would say in our lifetime and our children’s lifetime and our grandchildren’s lifetime, it’s a fallacy to believe the streams will clean up themselves. If we stopped everything for hundreds of years, I think nature would start to recover, but that’s not reality.”

As with other researchers, he sees the elimination of the more sensitive species, less able to adapt to the alterations of the habitat. Diversity gives way to the more general, more hardy species that become more abundant.

It is nature’s corollary to mom-and-pop stores downtown giving way to strip malls.