It took two botched police lineups, several erroneous witness statements and no physical evidence to lock up 14-year-old Anthony Williams for life in the shooting of a fellow teen he did not know. Twenty years later, a University of Tennessee at Chattanooga psychology professor helped unravel the case and set Williams free.

By Elizabeth A. Davis

Anthony Williams changed the course of his life forever when he went to a dance on Dec. 30, 1993, in his hometown of St. Louis.

It seemed innocent enough. A friend told him about the event, which was a fundraiser for the Phase Drum and Bugle Corps, and they decided to go check it out, meet some girls and have a good time. Williams was 14.

During the dance, someone pulled a chair out from under someone else, and a fight between two teenaged boys ensued. Lots of teens joined in, including Williams, who did not know the other two boys. Chaperones broke up the fight.

After the party stopped about midnight, Williams went outside and stood with some friends and other teens to wait for his ride home. Suddenly, the sound of gunfire rang out from the side of the building. People ducked for cover, and some of the teens, including Williams, ran. One of the boys who started the fight was struck in the forehead as he stood on the sidewalk. Cortez Andrews, a week shy of his 15th birthday, died two hours later at a hospital.

Police arrived on the scene and talked to people who were still hanging around. They gathered information about what people said they saw during the dance, such as Williams joining the fight, and descriptions of the shooter. At trial, an investigator said the information led them to Williams, despite a lack of physical evidence linking him to the shooting. Police never found the gun. Some of the people who claimed to have witnessed the shooting picked Williams out of police lineups.

Two weeks after the shooting, Williams was arrested and put in jail. In June 1995, Williams was tried as an adult, convicted of first-degree murder and given the mandatory sentence at that time of life in prison without parole. He spent the next 20 years hoping his innocence would be proven.

“Of course, when I was still young and naïve and didn’t understand the system, I really had a lot of faith that the truth would come out,” Williams says.

In 2014, it finally did. Thanks to a Supreme Court ruling, a tenacious defense attorney and the research of David Ross, a University of Tennessee at Chattanooga professor, Williams was freed on July 3, 2014.

“I remember most of it like it was yesterday,” Williams recalls about that night in 1993, regretting that he joined in the fight. “I wouldn’t have been forced to undergo what I went through if I had not gotten myself involved.”

Court Offers Hope

All of Williams’ appeals were denied, even an attempt in 2003 that demonstrated Williams’ case suffered from ineffective counsel. He had exhausted every legal remedy to have his conviction overturned. Then, in 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Miller v. Alabama that a mandatory sentence of life in prison without the possibility of parole for juvenile homicide offenders violates the Constitution. Missouri was among 28 states where life without the possibility of parole was a mandatory sentence for defendants 17 years or younger and convicted of homicide. Evan Miller, the complainant in the Supreme Court case, was 14, like Williams, at the time of the murder he was convicted of committing.

In Missouri, there were 84 people serving life-without-the-possibility-of-parole sentences handed down when they were juveniles. The state’s public defender’s office was overwhelmed with the prospect of reviewing all the affected cases for resentencing and sought private attorneys, including Jennifer Bukowsky in Columbia, Mo.

A criminal defense attorney, Bukowsky normally helps defendants avoid conviction instead of helping clients after they have been convicted. But she was compelled to assist and was given three dozen cases from which to choose a client. Bukowsky selected Williams’ case because it was the least heinous crime, and he was the youngest at the time of conviction.

“I felt like the case came to me for a reason,” Bukowsky says. As she studied the case files, Bukowsky began to consider that Williams, beyond deserving to be resentenced, might have been wrongly convicted. She was appalled at the lack of information in the police reports and the overall lack of investigation and time put into defending Williams.

“Witnesses said he was innocent, but they weren’t called to testify,” she says. “No one did the legwork for the defense on the onset.”

Bukowsky read the affidavits from so-called witnesses and was disturbed by what she found. Some witnesses changed their stories. Some never actually saw the shooting. Some of the teens who were standing with Williams at the time of the shooting and obviously saw him not commit the crime were not involved in the case.

But why did some of the witnesses choose Williams from a lineup? She pulled some articles about witness identification and landed upon research by UTC’s Ross, who trains law enforcement to conduct proper lineups and studies the idea called unconscious transference. In July 2013, Bukowsky contacted Ross to see if he would help.

“There was so much material and so little time,” Ross, UC Foundation Professor of Psychology, says about when he first learned about the case. “But it was the worst case I’d ever seen. This thing was a disaster.”

Bring in the Experts

Ross, along with graduate students Joe Jones and Dominick Adkinson, agreed to work on the case pro bono. The trio spent about 600 hours going through 1,000 pages of transcripts and other documents, line by line. Ross submitted a 54-page expert report to the court and then testified for more than two hours in February 2014 before Cole County (Mo.) Circuit Judge Daniel Richard Green.

The UTC team found many inconsistencies and errors in the way the police investigation was conducted. Chief among them were the procedures used to conduct the lineups at the police station. Since the time of the crime, the Department of Justice and International Association of Chiefs of Police have instituted guidelines for the collection of lineup identification evidence. Ross says these guidelines, if followed, could have changed the course of the police investigation.

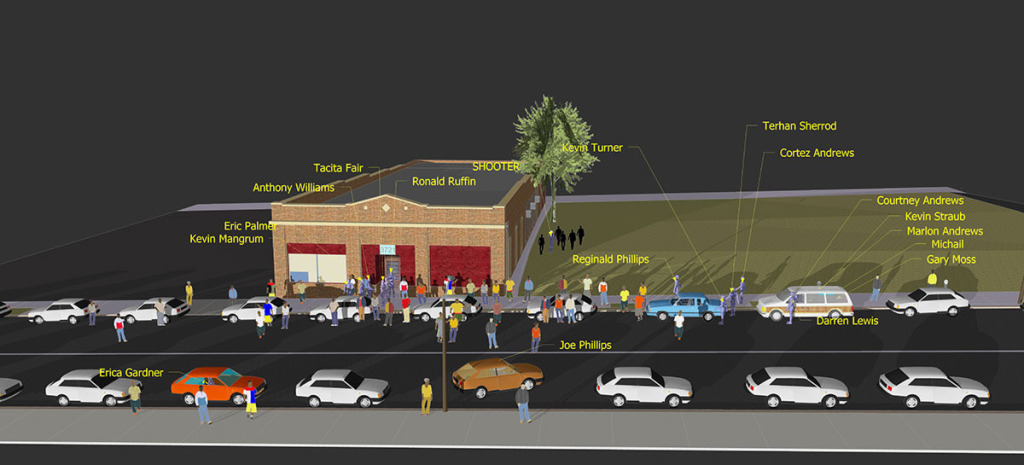

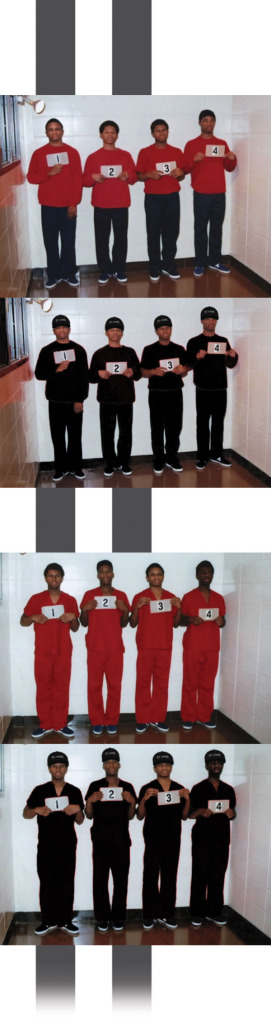

There were two lineups conducted by police. On Jan. 13, 1994, one of the witnesses was shown a lineup consisting of four young men wearing red shirts and black pants. In a second lineup shown to two other witnesses in February 1994, the men were wearing red jumpsuits. During the trial, it was revealed that the first witness actually saw both lineups and picked out Williams in each. “Repeated exposure to the same suspect in multiple lineups dramatically increases the probability that the suspect will be identified,” according to the report by Ross.

The construction of both lineups failed to match any of the witnesses’ descriptions of the shooter, which is prescribed by current lineup guidelines. The witnesses told police different descriptions of the shooter’s clothing, but most commonly the description was a black male wearing dark clothes and a ball cap with St. Louis lettering. None of the lineups were even close to this description. Each witness should have been shown a lineup of young men based on his or her description, Ross wrote in his report.

Ross also found fault in the way the police recorded the witnesses’ identifications or didn’t record them. “There is evidence that three of the four witnesses who make lineup identifications may have been shown more than one lineup, and that creates an enormous problem in terms of interpreting and understanding identification evidence,” according to the report. In addition, some of the witnesses were told to pick out the person they saw fighting at the dance, not the shooter. One of the more troubling parts of the trial transcript was this exchange with one of the witnesses.

The phenomenon known as unconscious transference is an area of expertise for Ross and was the subject of his thesis at Cornell University in 1989. It occurs when witnesses identify someone as an assailant because the person looks familiar instead of a clear memory of the assailant.

Many of the witnesses did not know Williams and had never seen him before the dance. However, some claimed they went to school with him but didn’t or thought he lived in an apartment complex where he never lived.

To combat unconscious transference, police must collect witness information quickly and correctly to avoid contamination, such as witnesses talking to each other about what they saw. “It is very easy to do it if you do it right, but it’s very easy to screw it up,” Ross says. “Once you contaminate it, you can’t go back.”

Ross also helped reconstruct the scene of the crime to show how some of the so-called witnesses could not have seen the shooter or the shooting because of where they were positioned on the street or sidewalk and the poor lighting.

Day of Judgment

Williams recalls watching Ross testify on his findings and says that “science was the equalizer” in the case. “Everybody there was amazed,” Williams says about the hearing. “The judge obviously saw the same things Dr. Ross saw.” The judge took several months to announce his findings, but in June 2014, Green threw out the conviction based on his conclusion that the prosecution withheld crucial evidence, and he gave the circuit attorney the option whether to retry Williams. Instead, prosecutors offered to let Williams go for time served on the lesser offense of second-degree murder.

While Williams maintains his innocence, he and Bukowsky believed this option would lead to a quicker release. On July 3, 2014, Williams was released from custody. Bukowsky hosted a party of 300 people on the eve of Independence Day for what was truly Williams’ day of independence.

The shooter in the case has never been found, although some think the shooter’s identity was known but covered up, and prosecutors in the original trial deny any wrongdoing. Bukowsky and Ross believe their conclusions were correct but worry there are many more wrongly convicted people because of poor evidence collection and incomplete investigations.

“It’s so shocking but all too common,” Ross says. “I’m called on these kinds of cases all the time to disentangle the errors. That is part of what I do.”

Bukowsky, as you might imagine, is covered up in requests from inmates seeking to have their cases examined, and she has enlisted the help of Williams. He has been working in her office since his release, learning to file and do other clerical jobs. Williams also reads through the letters Bukowsky is getting from inmates and makes recommendations on which stories sound compelling.

“This has been life changing for me and him,” Bukowsky says.

Photo by Anastasia Pottinger

Ross will get his first chance to talk to Williams in person when he joins Bukowsky and Williams at the annual training conference for Missouri public defenders in spring 2015 in Branson, Mo. They are serving as training faculty at the conference. Materials from Williams’ case will be used to train public defenders how to investigate, consult with experts and pursue leads and legal motions. “If our training helps prevent even one manifest injustice like what occurred in Anthony’s case, it’ll be well worth it,” Bukowsky says.

At 14, Williams studied German in school and was considered to be a very good baseball player with the chance to play in college or the pros. His mother was a teacher, and he earned his GED and worked in the law library while in prison. Still, the dramatic turn of events left him in a vulnerable position. “All of this happened so abruptly that I never gave a lot of thought to what I would do when I came home,” he says.

For the first time in his life, he has a job. Since being incarcerated at age 14, he had never lived on his own or driven a car before now. He likes living and working in Columbia, Mo., which has a slower pace than St. Louis. For now, he enjoys taking walks and eating at an outdoor café on his lunch breaks from the law firm.

“I’m grateful for Dr. Ross and Jennifer Bukowsky and all the vast array of supporters. I’m humbled by it all,” he says. But Williams shows no bitterness for the 20 years he spent in prison.

“I had a near-death experience. I’m happy to be alive and here and eager to experience life,” he says. “I feel like I’ve been resurrected.”