Surreal.

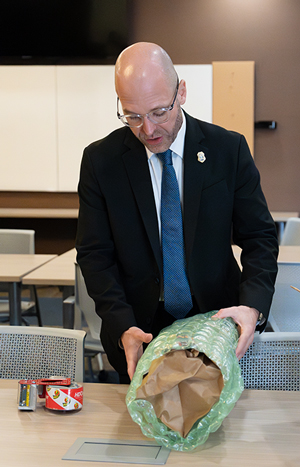

That is the word Tennessee Bureau of Investigation Special Agent Brandon Elkins uses to describe what it’s like to let families know that newly identified remains belong to their missing loved one. Elkins has worked in law enforcement for 20 years, and for 18 of those he had a keen interest in working on cold cases and unidentified human remains cases.

When he enrolled in the Institute for Public Service Naifeh Center for Effective Leadership’s Certified Public Manager program and knew a capstone project was required for completion of the program, he had an idea.

“I started asking questions, which is where any good project starts. I was asking, ‘How many cold cases do we have? How many unidentified do we really have?’ No one really knew,” he says. “That really surprised me.”

He started digging to find the answers.

“The first thing we had to get were the metrics. We had to understand how many cold cases we had and how many unidentified remains cases do we have,” Elkins says. “I hand sorted for about five days about 3,500 case files. Those old files dating back to the ’40s until about the early ’90s were not contemporized. They were not in any sort of electronic format.”

From his research, he determined that TBI had 479 cold cases and 14 unidentified human remains cases. He then submitted a proposal for a grant from the Bureau of Justice Assistance for prosecuting cold cases, specifically with hopes of using forensic genetic genealogy. With money from that grant, TBI paid overtime for analysts and hired a part-time former agent to help scan every hard copy case file to upload to the current reporting system.

“That is what I am doing with the skulls today,” he says, referring to skulls he was sending to a lab in Texas. “You’ve heard of Ancestry.com or 23andMe—forensic genetic genealogy is very similar. Random people across the world decide they want to learn more about their family, and they pay for a kit and submit their DNA through the kit. We don’t access those databases. The individuals choose to download their DNA and upload it to a couple of crowd-sourced databases. When the user uploads to one of those databases, they have the option to allow law enforcement to use their DNA to solve crimes to identify victims.”

Through the Bureau of Justice Assistance grant and two others, Elkins says TBI has identified about half of the 14 human remains cases. He works with the lab in Texas to help identify the remains. TBI presented a plan to expand its cold case effort and establish a unit in its most recent budget request as one of several opportunities for growth. Though it was not funded in this year’s budget, TBI leadership plans to continue championing this work and anticipates continuing to make a data-driven case for additional resources in future budget cycles.

“The project really exploded. I did not expect this to happen,” says Elkins. “For the past five years, I’ve been working full time overseeing the TBI Cold Case and Unidentified Human Remains Initiative.”

Elkins is the only person working full time on this project.

On one of the cold cases, TBI worked with the Sullivan County Sheriff’s Office to arrest and indict a suspect in a 1996 murder. They also brought an indictment posthumously in another case. Out of the 479 cold cases, they’ve been able to close about 10 percent permanently.

After identifying remains or solving a cold case, Elkins notifies the victim’s family.

“I would describe it as bittersweet,” he says. “Our director once said, and I’ve used it ever since I heard him say it because I couldn’t agree more, ‘We can’t provide closure to people, but we can provide answers.’ I feel like that is what my goal is, to be able to say, ‘We found them.’”