Public-health challenges posed by the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl have led to increased efforts at the federal and state level to combat the problem.

With a potency 50 times or higher than heroin, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency terms fentanyl a “dangerous threat to the safety, health and national security of the American people.” The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has reported almost 107,000 drug overdose deaths in 2021, with 67 percent of those deaths involving synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

Now, a new program in Tennessee will allow those dealing with drug addiction to test street drugs for the presence of the highly addictive substance, and. UT’s Substance Misuse and Addiction Resource for Tennessee (SMART) initiative is helping to gauge its effectiveness.

“We started seeing fentanyl play a role in overdose deaths as far back as 2016,” says Karen Pershing, Metro Drug Coalition executive director. “The problem now is that fentanyl is being added to so many different street drugs that a lot of people are ingesting it without even knowing.”

The Tennessee General Assembly voted in 2022 to decriminalize the use of test strips to detect fentanyl by people who use drugs. These were previously considered drug paraphernalia.

“Now that it’s legal to possess and use the test strips, any tool we can get out there to help people identify whether or not fentanyl is laced into their drugs will hopefully help them make an informed decision about their health,” Pershing says. “That’s why we discussed this with SMART.”

Jennifer Tourville, executive director of SMART, says the organization has produced a scientifically rigorous 20-question survey that can be given to people who actively use drugs.

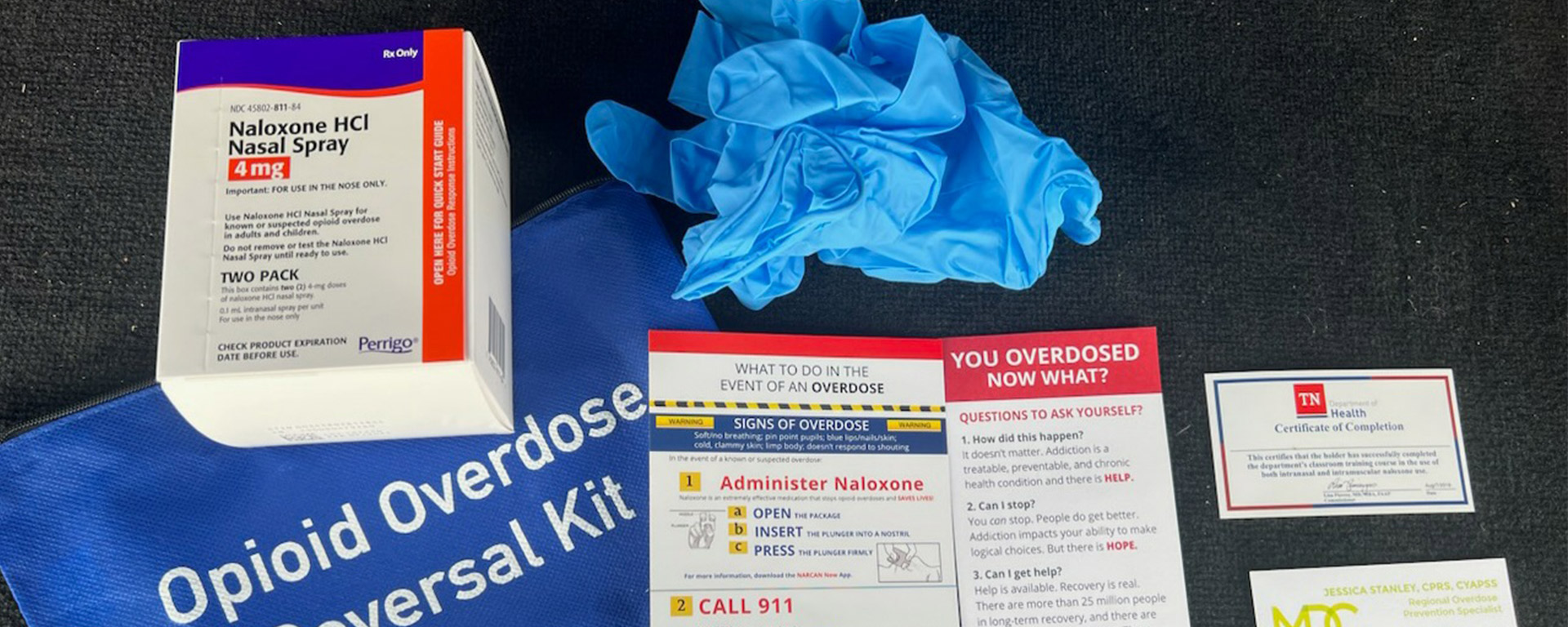

“First, we want to know what they will do if their drugs test positive for fentanyl. Will they not use the drugs, will they use at a lower dose, or will they ensure naloxone is available and that they are not alone? It’s our hope that, if they know that fentanyl is present, they’ll change their behavior,” she says.

Another set of questions in the SMART survey, Tourville says, deals with the number of test strips people need.

“The test strips cost about a dollar each,” Tourville says. “We want to know how many each person would need to adequately determine the presence of fentanyl in all of their drugs and if that cost is feasible over time.”

Getting the right number of test strips to the people in need is crucial, Tourville says.

“A lethal dose of fentanyl is only 2 milligrams, which is as small as a couple of grains of sand,” she says, “so it could be hiding anywhere in a batch of drugs. It’s what we call the ‘chocolate-chip cookie’ effect: The chocolate is in the cookie, just not distributed evenly. The person may need multiple test strips to ensure they’re not about to ingest a fatal dose of fentanyl.”

The survey will be conducted in Claiborne County, where the interfaith outreach group Live Free Claiborne runs a harm-reduction program.

“They’ve developed a lot of trust with their clients, and they’re willing to help administer the survey, so that will make a big impact,” Pershing says.

The Metro Drug Coalition also will administer the survey in Knoxville through its street-outreach efforts. Once the survey is complete and SMART analyzes the data, Tourville says, leaders will share the results with the Metro Drug Coalition and the state of Tennessee before publishing it in an academic journal.

“Overcoming issues related to substance use is one of the Grand Challenges facing our state,” Tourville says, “and we’re excited to be able to play a part in that effort.”