By Patricia McDaniels | Photos Courtesy UTIA

Bats. A highly infectious virus. Quarantines and mRNA vaccines.

They have changed the world in the past two years.

Who knew two years ago that a virus—frequent fodder for thriller movies and sci-fi novels—would transform the global society? Truth be told, lots of folks have been predicting the COVID-19 pandemic, or something similar, for years.

Global leaders in medical, scientific and political circles have long recognized that infectious diseases can threaten the world’s economic stability through their effects on human and animal life and biodiversity. Governments and scientific institutions have been collaborating to protect humanity’s health security through an integrated, unified effort loosely called One Health. The One Health concept recognizes that health issues must be addressed cohesively instead of independently.

The University of Tennessee joined the effort in 2019 with the bold launch of its own One Health Initiative—just weeks before Wuhan, China, leaders began to recognize that COVID-19 was a real danger.

With a unique balance of scientists, practitioners and stakeholders, the UT One Health Initiative focuses on animal and environmental health conditions that have implications for human populations. The UT One Health Initiative takes a holistic view of preventing disease through improving and appropriately managing the environment. “Humans, animals, plants and the environment are inextricably linked, with the health of one affecting the health of all,” states the initiative’s website. “Approximately 70 percent of emerging infectious disease cases in humans and livestock are a consequence of spillover events from wildlife. Similarly, humans play a role in animal disease emergence by facilitating global transfer of infectious agents, altering landscape conditions and adding environmental disturbances. Losses due to plant diseases can reduce global agricultural productivity by up to 40 percent for the five major food crops, thus undermining our ability to safeguard national and global food security.”

Ten years before the initiative was formed, faculty with the UT Institute of Agriculture (UTIA) established the Center for Wildlife Health to provide a multidisciplinary environment across UT Knoxville for the study of health issues arising from the interaction of wildlife, livestock, humans and the environment. Investigations include studies of the spread of Lyme disease, La Crosse encephalitis and a deadly skin pathogen (Chytrid fungus) that is killing salamanders and other amphibians. Other diseases that affect food and companion animals also are being analyzed.

In 2018, core members of the Center for Wildlife Health began discussions to transition the center’s interests to a stronger One Health focus, and in 2019, more than 50 faculty and scientists from multiple departments and colleges gathered to discuss how research efforts might be guided. From this, the strategic plan for UT’s One Health research and outreach began to take shape. With UTIA leading an internal investment totaling $2.5 million across several UT and Oak Ridge National Laboratory entities, the UT One Health Initiative was formed. UT deans continue to dedicate support for One Health scholars through release time and more than $450,000 in grants.

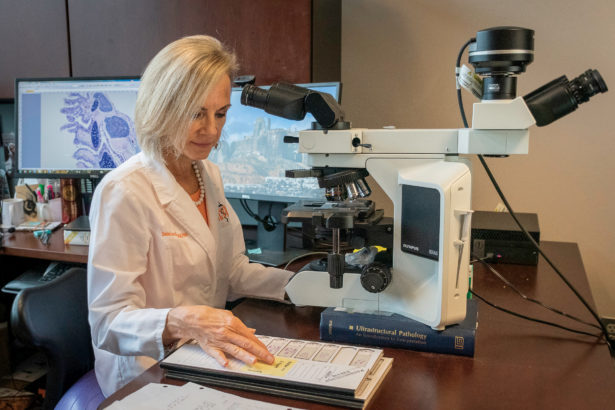

“Our vision for the One Health Initiative is to be a clearinghouse for translational discoveries that aim to improve animal, human and environmental health,” says Debra Miller, professor in the Herbert College of Agriculture’s Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries with a joint appointment in the College of Veterinary Medicine Department of Biomedical and Diagnostic Sciences. Miller serves as director for the initiative. “We believe we have the opportunity to be a global incubator for future generations of One Health experts across multiple disciplines and professions.”

UT experts and scientists with the Oak Ridge National Laboratory—ranging from biologists and sociologists to economists and computational scientists—are collaborating to explore all facets of human and animal conditions. UTIA’s concentration of animal scientists, wildlife biologists, entomologists, veterinarians, biosystems engineers and plant and soil scientists allows the university to approach the state, national and global One Health effort from the field as well as the lab. Experts from the UT One Health Initiative will gather their data on disease occurrence, environmental conditions and more from farms, forests, parks and communities. The rigors of big-data analysis and multi-scale mathematical modeling already allow researchers to quantify economic impacts and recommend environmental improvements or health safeguards.

“Not only is there a potential human health price to pay, there is an economic one as well,” says Miller.

According to the World Bank, zoonoses—diseases that have the potential to jump from animals to humans—have caused billions of dollars in economic losses each year in the U.S. alone. Cost estimates of the COVID-19 pandemic are staggering globally at trillions per year, not including the immense emotional impacts of the changes to ways of life and the loss of life involved. Chronic wasting disease, while still only affecting cervid (deer family) populations, could cost just the state of Tennessee between $50 million to $100 million annually due to a decline in hunter-associated expenditures.

The goal at UT is to create a One Health synergy across UT System campuses and institutes that can be expanded to support national and global One Health frameworks. Already the consortium is seeing success across a variety of disciplines, including a $7.2 million U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) grant to study ways to alleviate farmer stress and prevent depression and suicide. Heather Sedges, associate professor with Family and Consumer Sciences in UT Extension, crafted the proposal, attributing much of the success to One Health Initiative scholars, including associate directors Nina Fefferman, a professor in the departments of Mathematics and Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, and Carole Myers, a professor in the UT College of Nursing.

“We’re very excited the One Health Initiative is supporting researchers here at UT in tackling more challenging, integrated and far-reaching research questions and in launching more impactful programs,” says Fefferman. “By bringing together this uniquely multidisciplinary team, motivated to find commonalities across human, animal and plant systems, we can fill in gaps in our scientific understanding between siloed disciplines. We are building the capacity to respond to an ever-shifting world and help keep people safe, no matter what comes next,” she says.

Beyond research, the One Health Initiative is about education and outreach. In 2021, the initiative began hosting One Health lunch-and-learn seminars featuring local, national and international scientists. Seminars are currently scheduled through the Spring 2022 semester. The initiative also has developed a minor for undergraduate and graduate students wishing to develop skills to prepare themselves for careers in agricultural, environmental and human sciences, scientific policy and communication.

Younger learners and future scholars are included as well. Miller and others are frequent guests in primary and secondary schools introducing teachers and students to Backyard STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics) modules developed to expose youth to the science of the environment through hands-on learning of local and global ecosystems. An additional curriculum for 4-H learners focuses specifically on the science of outbreaks through the lens of the COVID-19 outbreak.

Stated simply, the UT One Health Initiative strives to provide real-life solutions for human, animal and environmental health in Tennessee and beyond.

To learn more about the UT One Health Initiative, including research directions, resources for educators, seminars and supporting projects, visit the website: onehealth.tennessee.edu.

Childhood Obesity

Nearly one out of five school-age children is considered obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Brynn Voy, a professor in the Department of Animal Science and a physiologist with a strong nutritional background, believes that the diets fed to chickens can be used to improve their health and welfare as well as to identify new ways to combat childhood obesity. With funding from USDA, Voy and her team are investigating how changing the type of fat consumed by a hen (or human mother) can be altered to reduce body fat and promote lean growth in chicks (and children). “It’s a dream to feel you could change the lives of others, particularly children,” says Voy. “In Tennessee, where we have Extension agents in every county, we have a pipeline to take this information straight to the citizens.”

Majestic Buck

What if the perfect 10-pointer wasn’t exactly perfect? What if he seemed unsteady on his feet? Overly thin? Drooling? Dan Grove, a wildlife veterinarian with University of Tennessee Extension who partners with the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency on issues affecting wildlife health, says the late-stage symptoms of chronic wasting disease—a neurological condition that affects cervid species like white-tailed deer—are heartbreaking and occurring with greater frequency. “Once infected, an animal literally wastes away,” says Grove. In 2018, Grove was among the field researchers who confirmed the disease in West Tennessee. While the disease is strictly confined to cervid populations at present, there is a fear that it could one day make the jump to humans. The Centers for Disease Control recommends that humans avoid consuming meat from animals infected with chronic wasting disease for that reason.

The Threat of Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria

In January 2019, David White, associate dean for UT AgResearch, began a four-year term as one of four new voting members to the U.S. Presidential Advisory Council on Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria (PACCARB). PACCARB’s mission is to advise and provide information and recommendations to the U.S. Secretary of Health and Human Services for federal programs and policies that aim to prevent and control illness and death related to antibiotic-resistant infections. White has worked extensively across federal agencies, international organizations and academia to coordinate antimicrobial resistance issues. White will serve with PACCARB while also maintaining his role with UT AgResearch.

Mosquitoes and Ticks, Oh My!

Becky Trout Fryxell, an associate professor of medical and veterinary entomology in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, is working to stem the rise of La Crosse encephalitis, the most frequently reported mosquito-borne disease of children in the U.S. Severe infection can lead to seizures, paralysis and even cognitive disorders and is primarily reported in young children in East Tennessee and throughout Southern Appalachia. Trout Fryxell has received U.S. Department of Agriculture funding to create a community-driven surveillance network for mosquitoes that carry La Crosse virus. The program uses student-driven inquiries and classroom learning to engage sixth-through 12th-graders directly with the science of mosquito biology and behaviors as well as public-health science about infectious disease and its transmission.

As part of the program, the students test a hypothesis by monitoring and identifying data about specific target populations of mosquitoes carrying La Crosse virus, which causes La Crosse encephalitis (LACE). Program participants help identify mosquito populations for management, thus reducing LACE cases in the region. Thus far, 15 trained educators have guided more than 500 students on classroom independent experiments to monitor and assess mosquito populations at their schools and generated high-quality datasets used by UT graduate students. Their data will be used by public health professionals in various ways. Trout Fryxell and colleagues will plan, develop and evaluate efficient, cost-effective and targeted mosquito-control efforts. To learn more about the program, visit www.megabitess.org.

With a different grant from the Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research, Trout Fryxell and a research team are tracking the spread of the Asian longhorned tick, which frequently forms large infestations (1,000-plus ticks) on warm-blooded host animals. A severe infestation can kill an animal through blood loss or reduce an animal’s growth and production. This research led to the discovery of the Asian longhorned tick in Tennessee as well as methods for management, modes of dispersal and mechanisms for its surveillance. Currently, Trout Fryxell collaborates with Virginia researchers to improve detection methods for Asian longhorned ticks infected with Theileria orientalis Ikeda and plans to study how infected ticks disperse across the landscape using ecological, epidemiological and genetic analyses with the purpose of identifying methods to prevent, detect and respond to future outbreaks.