Jon Manchip White: Author, Screenwriter and Spy

By Fred Brown

Fred Brown interviewed Jon Manchip White at his Knoxville home in June 2013, several weeks prior to his death, and attended White’s memorial service. The story was meant to be a profile, but what follows is a tribute.

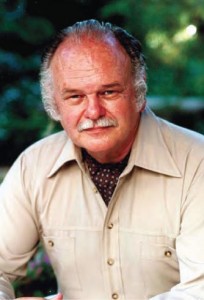

Welsh writer Jon Manchip White, with his ascot, a bristly white mustache, and pleasant and gentle demeanor, never looked the part of a British spy. But he spent four years with Britain’s Foreign Service, arranging meetings for people in distant corners of the world for England’s spy masters.

Well, of course, that fit rather well with the rest of his resume: BBC radio and television scriptwriter, poet, novelist, playwright, global traveler and professor of English. He also was a friend of some of the world’s best-known authors, among them C.S. Lewis, C.S. Forester, Agatha Christie, James Hanley, Graham Greene, Dylan Thomas, Welsh poet Roy Campbell, and American authors Tennessee Williams and Nicholas Delbanco.

Screen legends John Wayne and Richard Burton also were acquaintances. Once, while working in Spain on a movie script, White and “The Duke” were walking along a street in Madrid when it struck him that he was “actually walking down the street with John Wayne, and people were stopping to stare.”

At the time of his death in Knoxville on July 31, 2013, from respiratory problems, the 89-year-old White retained his British passport but had become a U.S. citizen. He retired in 1994 as Lindsay Young Professor of English in the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, English department, where he taught for 17 years and was the founder of the creative writing program. Prior to UT, White held a similar post at the University of Texas at El Paso, where he began its creative writing program.

“There should be an art of living just as there is an art of writing”

—Jon Manchip White

White led a life of letters, as his 1991 memoir, A Journeying Boy, so succinctly phrases it. But he was so much more than a mere writer. He was a master at living.

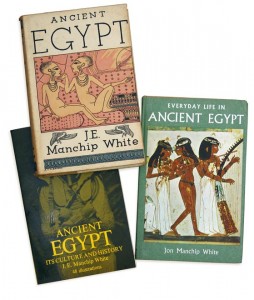

His credits include more than 30 books of fiction, poetry, history, travel, archaeology and anthropology, as well as numerous movies and television plays. He was the BBC’s first television story editor.

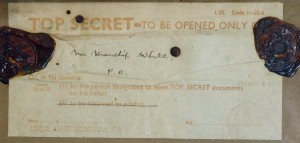

He was very proud of the oath he had signed with MI5 to keep silent about his work with the Foreign Service. The framed signature, in invisible ink, was on the wall in his study, along with other photos of a life well lived. But a writer had to do more, he once wrote, than “simply leave words on paper.”

To fully experience life, he said, one must also travel and have lots of music. The Welsh, he wrote, were not only gregarious storytellers but also lovers of music. His constant urge to move on, to see what lay around the next bend in the road, came naturally for White, a member of a noted Cardiff, Wales, seafaring family. He was born into “Britain’s post-Imperial generation,” known in England as “The Slump” and in America as “The Great Depression,” His lineage of seafaring stock settled around the Bristol Channel and the Coast of South Wales and included the ancestor Rawlins White, who had owned a fishing fleet but was burned at the stake in 1555.

While most of the regular reporters were off at war, White reported on the courts, movies, sports; dodged the bombs; and had “an altogether marvelous time.”

White’s father, Gwilym (William) Manchip White, who was part owner and managing director of the Taff Vale Shipping Co. of Cardiff, contracted tuberculosis about three years after White’s birth. When White was 8, the doctor recommended that he be moved to England to escape the virulent tubercular environment of the home, and he was packed off to an English boarding school some 20 miles north of London. Thus, from that early beginning, White became the journeying boy, traveling back and forth between Cardiff and London.

Those frequent train rides from England to Wales and back during the early World War II years gave him a sense of being connected to both places. But there were terrifying memories as well.

During the horrific German air raids of the London blitz, he and his aunt held his mother’s hands in a bomb cellar in their home. “Some of the bombs merely belched and growled and pounded on the earth like surly animals,” he recalled, “but others, particularly the land mines that floated down by parachute and exploded in midair, sounded like a herd of elephants crashing through a tin.” By this time, the young White was a correspondent for the Western Mail in Cardiff. While most of the regular reporters were off at war, White reported on the courts, movies, sports; dodged the bombs; and had “an altogether marvelous time.”

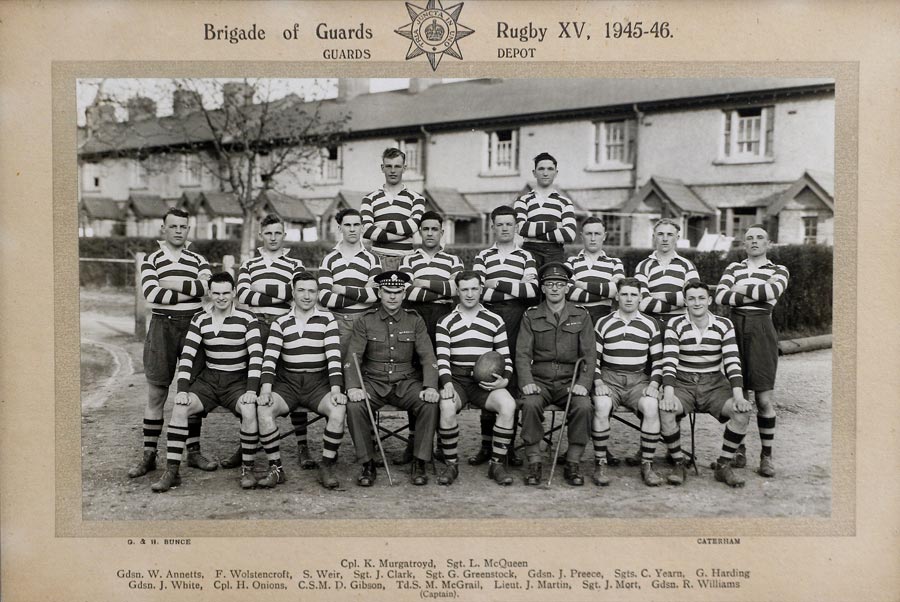

Not long after his father’s death in 1941, White received a scholarship to St. Catherine’s College at Cambridge, where he studied English literature from 1942-43 until he became of military age. Like his ancestors, White went to sea with the Royal Navy, serving on ships guarding convoys and ferrying troops and war materiel across the dangerous Atlantic Ocean. Near the end of the war, he was sent to India, still a British colony, where he grabbed a post with the famed Welsh Guards in one of the five regiments of His Majesty’s Foot Guards.

Victory in Europe Day, May 8, 1945, turned into a serendipitous meeting and a romantic love story. In the jubilant streets of Cardiff, crowds were going wild, kissing and hugging. White and a female friend were “rocking from side to side and slopping our drinks and singing our heads off,” he said, when they made it inside the bar at the Claude Hotel, a “three-story Edwardian structure” filled with people. Outside the streets were a “seething mass of men and women, young and old,” celebrating the end of the war. Like White and his female friend, more than half of the revelers were in uniform. Then, over in a corner, with the May sunshine slanting in through leaded-glass windows, he caught sight of a small dark-haired girl in a nurse’s uniform, surrounded by a gaggle of servicemen. The girls of Cardiff, he wrote, were known for their beauty, but “this one struck me as beautiful enough to take her place beside the ‘gentle gold-torqued women’ who throng the pages of the Mabinogion” (heroic medieval Celtic tales).

Not long afterwards, he and Valerie Leighton married and remained husband and wife for 40 years before she died in Knoxville with a brain aneurism. White spent a decade tending to his bedridden wife before her death. “She was the most beautiful girl in Cardiff,” he wrote in his memoir.

In 1960, White had taken a job with Samuel Bronston, an American filmmaker producing a series of screen epics in Europe. The job put White in Paris for one year and Spain for four when the Bronston Company was filming El Cid, 55 Days at Peking and The Fall of the Roman Empire. This is where, one of his friends said at his memorial, “Jon put words in the mouth of Ava Gardner.” Ever the journeying boy, White took the opportunity while in Spain to tour the country in “Siegfried,” his vintage Mercedes 540K. He bought the car in Madrid and drove it for more than a decade across both Europe and much of America. He also spent time in South Africa with a British film company and visited Namibia, which inspired his first travel book.

At 40, he was ready for real change. He intended, he says, to head for America. He had come to know Cleanth Brooks, then a cultural attaché at the American Embassy in London, who recommended White for posts in American universities. Brooks was an established poet, critic of Southern literature and English professor.

After short stints in California and Arizona, White landed the job at the University of Texas at El Paso, giving him the opportunity to investigate the Native American culture, which allowed to use the knowledge gained from his archaeological studies at Cambridge. He spent a decade at UTEP from 1967-77 before taking a job at UT Knoxville as a professor of English and head of the creative writing program. Although writing was the core of his life, it wasn’t all of it.

“There should be an art of living just as there is an art of writing,” White wrote in his biography. And what a life: His Knoxville home contains a “suit of lights” he purchased in Spain and swore that a famous matador once wore in a Madrid corrida. At home, White loved American jazz, hats of every size and description—especially the Western cowboy version—and books, including many first editions written by famous British authors. He also loved racecars and other sports, especially British “football” and rugby. But his greatest passion was music. His longtime friend, Patricia Carter-Zagorski, an associate professor of piano at the UT Knoxville School of Music, says White knew as much as and more than many of those teaching music at the university.

“He was a gifted spirit,” she told a large crowd at his memorial service at Knoxville’s famous Foundry, which ironically had been founded by Welsh iron men of the 19th century. “He was a Renaissance man,” she said. “He could hum the nine symphonies of Beethoven.” At the time of his death, he had been re-reading all the works of Shakespeare and Dickens and others. He was also working on a final memoir of his life. He realized the ink well was running dry, his daughter Rhiannon said at the memorial. “The night before he died, he told me he could no longer write, and that was the end for a writer.”

Nicholas Delbanco, White’s friend for more than three decades, said he came to know him probably better than most through the letters they exchanged, sometimes daily, over those many years, adding to more than 1,000 documents. Delbanco, the Robert Frost Distinguished University Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Michigan, is currently putting together those letters in book form to be published next fall. He cited White’s versatile interests from archaeology and Egyptology to art history and Native American customs. “We have lost a matchless master and shall not look upon his like or near equal again.”

Then Delbanco read from one of White’s last letters, which talked of his fading life and past glories. “My glory,” White had written, “was having such friends.”