By Fred Brown

Photography by O’Neil Arnold

World War II was over, and the boys were coming home by the trainload. Charles F. Herd, a wounded veteran from Sparta, Tenn., fought with the 84th Infantry Division in battles across France and Germany. Like other veterans of his age, he was ready to put the war in the rearview mirror and move on with his life.

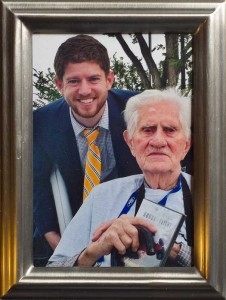

Herd, now 92 years old, had been among the many University of Tennessee Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) officers summoned to active duty in the Army during the war. He departed shortly before Christmas 1942 for training at Fort McClellan, Ala., missing his graduation ceremonies at UT Knoxville, and then was sent on to Officer Candidate School at Fort Benning, Ga.

As a freshly minted second lieutenant, he was assigned to the 84th Infantry Division, known as “The Railsplitters,” and stationed with the 335th Regiment with a heavy weapons company. He was on active duty from 1943-1946.

As a freshly minted second lieutenant, he was assigned to the 84th Infantry Division, known as “The Railsplitters,” and stationed with the 335th Regiment with a heavy weapons company. He was on active duty from 1943-1946.

The division landed at Omaha Beach on Nov. 1, 1944, and saw its first combat a little over two weeks later at Geilenkirchen, Germany, as part of the larger offensive in the Roer Valley, north of Aachen, according to the 84th’s official history at the U.S. Army’s Center of Military History.

Herd says that, while moving toward German lines with the 84th, he was wounded when struck by fragments of anti-personnel bombs from attacking German warplanes.

“Since I could not walk,” he says, “I called for a medic, who put me in a Jeep to be taken to an aid station, where the doctors removed a metal bomb fragment about an inch long from my right foot. Other fragments had hit me in the back.” He was in hospitals in Paris and England before returning to the 84th, which had reached the Elbe River in Germany by this time. Later, he was transferred to command “internee” camps in Germany before returning home.

Internee camps, he says, were not prisoner-of-war sites but places that held those suspected of war crimes of one nature or another. At one of the camps where he was in command, an internee painted a watercolor of the dashing lieutenant, a portrait he still cherishes today.

After the war, Herd, who graduated from White County High School in 1939 and from the University of Tennessee in 1943, had decided he wanted to be a writer or in the communications field. At UT, Herd had worked part time for the UT News Bureau and was a student announcer on UT radio programs. He was also on the staff of the Orange and White, the former name of the student newspaper, and created a newsletter for non-fraternity students. Using the GI bill in 1946, he tried Columbia University in New York and even had a few classes in Radio City taught by NBC staffers.

But by 1947, Herd felt that something was still missing in his life. So he decided to leave New York and head to Iowa where the Iowa University Writers Workshop was in full progress turning out top-tier writers. Among Iowa’s recent famous workshop alums was Southern writer Flannery O’Connor, who was well on her way to making a big name in American literature just as Herd was arriving on campus. He says that this is when his life was perhaps changed by a comma.

Herd yearned to write a graduate thesis that featured creative writing, he says. That’s why he left Columbia in New York in 1947 and set off for the University of Iowa. “I wanted to use original writing such as a novel or short stories rather than do a research thesis—something like, ‘The Use of the Comma in Shakespeare’s Comedies.’”

In late 1947, while on the Iowa campus, Herd met Carrie Belle Morris (Knoxville ’47), who was at Iowa on a fellowship. They married in 1949. After writing an original thesis of short stories, Herd graduated from Iowa with a Master of Fine Arts.

After Morris finished her master’s degree, she went to Tuscaloosa to teach at the University of Alabama for a few years and then landed a teaching post back at her alma mater. From Knoxville, Herd launched a career that eventually took him and his wife around the world.

Starting with an entry-level job at the Knoxville Chamber of Commerce (1949-66) as public relations director, he eventually became the chamber’s executive vice president. Herd also was instrumental in fostering the popular Dogwood Trails and Dogwood Arts Festival in Knoxville, which remains an annual event.

While heading up the chamber in Knoxville, Herd was elected president of the Tennessee Association of Chamber of Commerce Executives. He was a member of the association from 1953-66. This put him in an active position with the Southern Association of Chamber of Commerce Executives, where he was president from 1967-68.

It wasn’t long before Herd learned through his friends at the Southern Association that the top job at the Louisville, Ky., chamber was opening. After a visit to the historic Kentucky city, Herd accepted a position as Louisville’s executive vice president and eventually as chief executive officer (1966-83). “We fell in love with Louisville,” Herd says about the city made famous by the baseball bat known as the Louisville Slugger.

Just as he had been instrumental in starting the Dogwood Arts Festival in Knoxville, Herd kicked off the Louisville Heritage Festival Weekends and persuaded the chamber to sponsor the Leadership Louisville Program. He eventually was elected president of the Kentucky Chamber of Commerce Association, serving two terms. He also served as the head of the American Chamber of Commerce Executives in the early 1970s.

After retiring as CEO of the Louisville Chamber in 1983, he was appointed as a member of the Senior Executive Service Corps of the U.S. Chamber. With the service corps, he helped nearly 100 local and state chambers nationwide in the accreditation process. At the same time, Herd also served as a volunteer for the International Executive Service Corps, where he assisted the chambers in Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Kenya and Gambia. Later, Herd accepted assignments in Ecuador and elsewhere in Africa.

Last year, he was chosen to visit Washington with other World War II veterans as part of the “Honor Flight” program. And, despite his 92 years, the Herds return to Knoxville to visit family whenever they can. “And,” especially, he says, “to see a UT football game.”