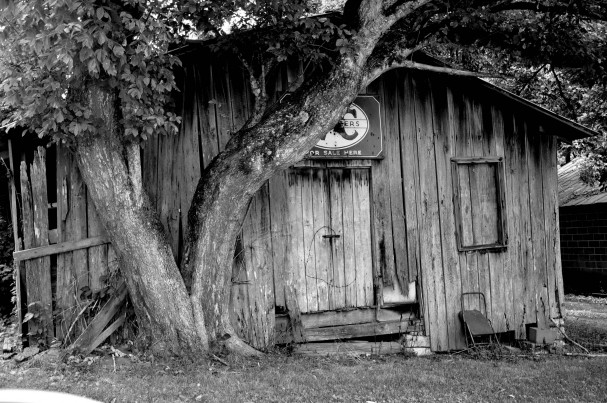

Featured photo: Old grocery stores were once common places along highways in rural Appalachia. Most were built facing the adjacent roadway with the store name painted on the side of the building. One such relic is the Dixon Grocery building in the Sunrise Community along Highway 11-W in Grainger County. The grocery closed in the mid 1950’s and since then, weathering and non-use has gradually left the building in disrepair.

By Fred Brown

Harry L. Moore, retired geologist with the Tennessee Department of Transportation and former head of its geotechnical engineering department in East Tennessee, has spent years photographing Appalachia’s disappearing landscape and illustrates this story with his photos of the region. Moore (Knoxville ’71, ’74) is the author of many papers and four books on the unique geology of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and other geologic phenomenon across East Tennessee. For this project, Moore spent months driving, hiking and wandering the region’s back roads to capture a past life that is slowly dissolving into history. He chose to interpret this story in the style of Walker Evans, the masterful Depression-era photographer, shooting the scenes in dramatic black and white to evoke more emotionally the region’s passing culture.

Growing up in Appalachia before, during and just after World War II was to live in a village-like atmosphere, perhaps even an age of innocence. Feed and seed stores, where old men cracked jokes and floors creaked and groaned under foot traffic, dotted towns and country roads, some of which were still dirt and gravel.

Hillsides rambled in great greenswards, rolling young and vibrant. Crops grew in a patchwork of greens and browns, yellows and whites. Tree lines identified huge swaths of a farmer’s boundary. Or, maybe a rock wall isolated one section from another.

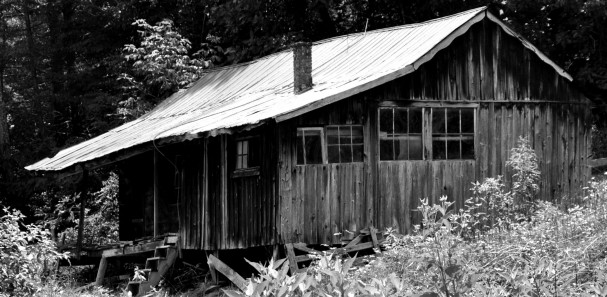

Wood-shingled crib barns, tobacco barns or the exquisitely designed cantilevered barns were stalwart structures of the time. They stored hay, cattle and brown-leaf tobacco, hanging like drying leather from the rafters.

That was Appalachia of the pre- and post-war years. Not today.

“Disappearing farms is the biggest change I have seen in my life time,” says Glenn Cardwell, 83, who was born in historic Greenbrier, a green valley in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park where he spent 34 years as a park ranger.

The valley of his youth was marked by small farms, smokehouses, grist mills, cornfields and pastureland, in reality a village life. But, when the village disappears, so does the culture. “I didn’t know we were in a Depression,” Cardwell says, remembering his childhood. “We made do or we did without. We were a sufficient society, even though it was hand-to-mouth. It was a good life,” says Cardwell, who is now the mayor of picturesque Pittman Center near Sevierville, Tenn., a mountain village holding close to its mountain heritage.

“Losing the farms has changed our way of life,” says Cardwell. “The other thing that changed us is that the government bought up the farmer’s allotments of tobacco. Now, our tobacco barns are empty.”

Today, he says, tourism is king in East Tennessee, especially near Sevierville, Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg, the small mountain town nestled in the bosom of the national park. “There was no commerce in those early days. It was rural, wherever you looked.”

Not today. Commerce, as he says, has pushed aside whole farms and farmlands. Instead of growing crops, acres of land in East Tennessee grow houses. In the case of Pigeon Forge and Gatlinburg, motels, tourist-oriented recreation and entertainment have sprouted like mushrooms.

But East Tennessee is not the only part of Appalachia that is facing rapid change. So is the land of the grand division of West Tennessee. Paul Richardson is a 92-year- old retired farmer and veteran of World War II who grew up and farmed in West Tennessee in the area of Crockett County. He worked behind a pair of plow mules all day breaking up a field.

Main crops, he says, were corn, cotton, hay and oats. He hand-chopped weeds out of the rows of cotton and picked the cotton by hand. The biggest change in his life, he says, is the mechanization of farming. His family had four mules and farmed 50 acres in the 1920s and 1930s. Today, one person can farm 1,500 acres alone, using computers on very large equipment and understanding the intricacies of soil science, fertilizers and the mechanization of production.

Rural living during the 1930s and ’40s was not easy. Homes did not have conveniences we take for granted: Water was hauled from a well or cistern; heat derived from wood, oil, or coal stove; light was from oil lamps; bathrooms were outhouses; houses were rarely insulated.

In fact, Richardson says electricity arrived in his section of Crockett County in late 1930. In East Tennessee, the Tennessee Valley Authority, created in 1933, provided electricity for the region, bringing lights for the first time to many a darkened household.

Most all communities had a school, church and a store, which sold all manner of necessities. But the demise of the rural community school, Richardson says, began the decay of the rural community. Education was highly valued, and schools were usually located in the center of the community where children would not have to walk or ride a bicycle more than a few miles to attend. There were no car pools.

Community stores, says Richardson, were commonplace in most rural areas, providing necessary staples like flour, sugar, meal, bacon and coffee. Many stores were a combination country store and hardware outlet. Some even bartered for fresh chickens and eggs and even sold caskets, nails, garden tools and barbed wire. And most stores offered credit throughout the year, relying on being paid after fall harvest season. Big box chains run by giant brands have replaced the hardware and general purpose store.

A very real perspective of the change in Appalachia concerns the number of farms and acreage in 1920 compared to the latest figures for today. In 1920, East Tennessee had roughly 76,376 farms on 6.1 million acres compared to 32,139 farms on 3.4 million acres today.

In general, says Tim Cross, dean of the University of Tennessee Extension, farms are losing the battle to subdivisions, shopping centers and urban expansion.

“The best farmland is the bottomland, and the best place to build a house is on flatlands. Clearly, all of agriculture has changed over the last 50 years, and it’s been revolutionary in many ways.”

Technology, he says, allows fewer farmers to produce more food. “That is good,” says Cross. “It allows us to feed ourselves at lower costs. But the downside is that adoption of technology has largely favored the growth of larger farms. We have seen the consolidation of farms and simultaneously the loss of farmland due to urbanization and housing development.”

The old home place is passing into history in Appalachia as cities and towns spread their reach.

Like fog rolling in from a river, covering the low-lying land and blurring the nature of the countryside, change is altering the face of Appalachia.