By Elizabeth Davis

Bill Harwood’s Reporting Career Outlasts Shuttle

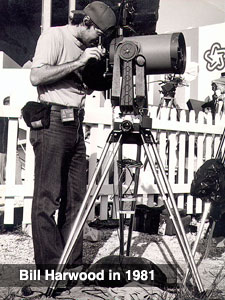

Bill Harwood’s first viewing of a space shuttle launch was anticlimactic. The clock ticked down to T minus 5 minutes and stopped due to a mechanical malfunction. The launch was scrubbed and rescheduled.

That meant Harwood (Knoxville ’82), then a student and reporter for The Daily Beacon newspaper, and a photographer had to drive back to Knoxville. But they made the trip to Cape Canaveral again a few days later to watch Space Shuttle Columbia actually take off.

“It was unbelievably loud,” Harwood recalls. “The shirt I was wearing vibrated.”

This was Nov. 12, 1981, the second launch of the space shuttle or STS-2, in NASA vernacular. Even though he didn’t know it then, Harwood had discovered a career that would outlast the 30-year run of the space shuttle program.

Harwood is the senior space consultant for CBS News, a position he’s held since 1992. Based at Kennedy Space Center in Florida, he maintains the website CBS News:space and is seen on camera for interviews discussing NASA missions and programs. Harwood also contributes to The New York Times, CNET and Spaceflight Now. He is co-author of the book Comm Check about the 2003 Columbia disaster that killed seven astronauts.

Harwood was one of three journalists to receive the Space Foundation’s 2011 Douglas S. Morrow Public Outreach Award for contributing to the public’s understanding and support of space programs. Previous recipients include actors Tom Hanks and Leonard Nimoy and the late screenwriter and producer Gene Roddenberry.

Harwood has covered NASA as a professional reporter since 1984. In that time, he witnessed 129 of 135 shuttle launches.

Unchartered Territory

“Nothing ever equaled the first one,” he says.Now Harwood’s career is in unchartered territory. There are no more space shuttles. The space shuttle program ended in July 2011 when the Atlantis touched down in Florida.

Of course, he has covered other aspects of space such as the International Space Station, discoveries of other solar systems and planets, national space policy decisions and the plans for deep space exploration and commercial space travel.

“There are major changes for NASA,” he says. “Now the focus will be on deep space.”

Harwood’s career didn’t begin as one might imagine. He did not dream of becoming an astronaut. His goal was to be a science writer.

He grew up in Nashville and followed the Gemini and Apollo programs as a youngster. His older brother turned him on to science by taking him to search for fossils and by reading science fiction.

“I never dreamed I’d have anything to do with it,” Harwood says.

He went to UT on what he calls the 10-year plan, which actually took closer to 12 years. He found work at the Beacon and went on some exciting assignments such as riding in a KC-135 while it was re-fueling a B-52 bomber in mid-air.

He fondly recalls Paul Ashdown, professor in of journalism and electronic media, teaching him how to write a lead and spending late nights at the Beacon to get the newspaper out the next morning.

“It was a great learning experience,” he says.

“Challenger brought that home to me.”

The trip to the second space shuttle launch served him well. Upon graduation, he was hired by United Press International (UPI) to work in the Columbia, S.C., bureau. Still interested in the space shuttle, Harwood went on his own dime to see another launch. At the same time, the news wire services UPI and the Associated Press decided they needed to staff the launches and locate bureaus at the space center. When UPI asked if anyone on staff knew about the space program and wanted to cover it, Harwood was more than willing.

He moved to Florida in 1984. “And I’ve been here ever since,” he says.

Clearly, Harwood harbors some sentiment about the shuttle program. The mere physics of a launch and orbit are astounding, and the shuttle is considered one of the most complex machines ever built.

Clearly, Harwood harbors some sentiment about the shuttle program. The mere physics of a launch and orbit are astounding, and the shuttle is considered one of the most complex machines ever built.

“On TV it looks like slow motion,” Harwood says of a launch. “It’s 4.5 million pounds going from zero to 100 miles an hour – straight up — in eight seconds.”

Once in orbit, the shuttle travels 5 miles a second, which is the equivalent of passing over 88 football fields a second.

“The shuttle had an element of danger to it, an enormous amount of energy,” he says. “The slightest hiccup has fatal consequences.”

“Challenger brought that home to me.”

Despite the dangers, the 1986 shuttle explosion shocked the nation. The seven astronauts, including teacher Christa McAuliffe, perished.

For a reporter, it was a monumental news event, says Harwood, who was writing for UPI at the time.

“It was gut-wrenching,” he says. “It happened right out the window here.”

Then he adds: “It’s not remarkable there were two disasters; it’s remarkable there weren’t more.”

With so many successful launches and landings in three decades, it may be hard for the public to appreciate the accomplishments of the program. Aside from the technology involved in and that resulted from the shuttles, the most important might be the ability it gave two former Cold War rivals to travel to and from the International Space Station.

How successful will NASA’s next projects be? Will private citizens be able to travel into space? Where will they go?

He may not go with them, but Harwood will let us know if they reach their destination.