Jack McConnell doesn’t have anything against golf; he’s played a few rounds in his day. But it takes too much time, the “retired” physician and healthcare activist says–time he could spend helping a sick neighbor or planning a clinic to provide free healthcare in Kenya.

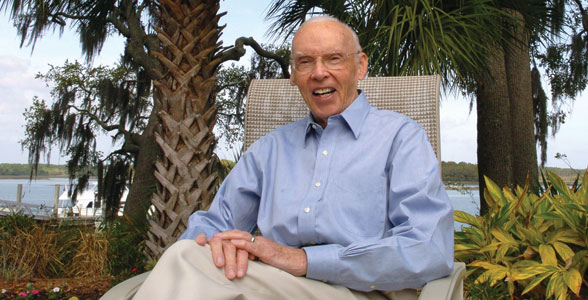

McConnell (Health Science Center ’49), founder of the original Volunteers in Medicine Clinic at Hilton Head Island, South Carolina, would rather help start more free clinics instead of putting or puttering–pastimes more closely associated with his age of 82.

Tennessee Alumnus featured McConnell in 1996 when his prototype Volunteers in Medicine Clinic was just 3 years old. His idea was smart and simple: retired healthcare professionals who moved to Hilton Head, an upscale oceanfront enclave, soon tired of endless days of golfing. They would gladly volunteer their time and talent to provide free healthcare for their less fortunate neighbors. McConnell got the permissions and approvals to make it happen, and the clinic’s success turned heads all around the U.S. Now there are more than 50 Volunteers in Medicine clinics throughout the nation, all built on the UT graduate’s concept.

In addition to healthcare, the clinics dish up a generous serving of human kindness and respect. McConnell’s philosophy is to welcome “friends and neighbors,” not “patients,” for medical and dental care. The Hilton Head Clinic cared for 8,000 people last year–29,000 patient visits–almost double the number projected in 1993.

The number of people treated “has increased so much that we needed to purchase the building next door to care for them,” McConnell says. “We have enlarged our clinic space for those with psychiatric, mental health, and social problems, as well as our diabetic clinics.

“That gives us more room to care for those who need obstetrical care or minor surgery, those with hypertension, orthopedic issues, or eye problems. We have also more than doubled our dental area and service with five rooms and children’s dental protective procedures.”

McConnell was born in West Virginia, but his family lived in several towns in Georgia, East Tennessee, and Virginia since his father was a Methodist preacher who was transferred frequently. As a young man, McConnell attended the University of Virginia before enrolling at the Health Science Center in 1945. He did postgraduate training in pediatrics at Baylor College of Medicine and attended Harvard and Columbia business schools.

McConnell is accustomed to getting things done. He directed the development of the tine test used to detect tuberculosis, participated in the early stages of the development of the polio vaccine, directed the program for the development of Tylenol tablets, created and directed the program for the first commercial MRI system in the U.S., and cofounded the Institute for Genomic Research.

His resume includes innumerable honors and awards reflecting his lifetime of accomplishments and service. One of the most recent is the 2007 AARP Impact Award, given to “people who make the world a better place.”

Although McConnell says he “mostly stays at home” in Hilton Head, his mind has been busy with plans for a free clinic across the sea in Kenya. Representatives from a large Kenyan church visited Hilton Head and went away wanting to copy the Volunteers in Medicine model.

“I’m about ready to send them a proposal,” he said in early March. “I’ve been reading the Kenyan health laws–they’re about three inches thick!”

According to McConnell’s plan, doctors from VIM clinics in the U.S. would begin this summer flying to Kenya and volunteering at the clinic for a week, with the enticement of free tours of the area after their work is finished.

If there’s one thing this energetic octogenarian has learned, it’s “don’t take no for an answer.” When he originated the idea for the original Volunteers in Medicine clinic, there were many obstacles–financial, political, logistical. But he kept his focus on the Hilton Head friends and neighbors who needed healthcare. A balky state medical board threatened to deny the clinic’s approval, despite copious groundwork laid by McConnell and others.

“I was never so despondent in my life as I drove back from Columbia [the South Carolina state capital] after that meeting,” he recalls. But by the time he got to the Hilton Head turnoff, he had figured a way around the problem, enlisting the aid of a state legislator and the governor. The governor later spoke at the clinic’s dedication and endorsed the concept of free healthcare for the needy, citing the experience of his father, a country physician, who at his death was owed far more money than he had ever collected.

“You can’t be weak-kneed” when you know your goals are worthwhile, McConnell declares. His payback has come in the form of genuine friendship and appreciation on the part of the VIM clinic’s clientele. One of the first people treated there continues to visit–and financially support–the clinic.

“A lady came to the clinic on Saturday before we were to open on Monday and said she wanted to be our first patient,” McConnell recalls. “I told her if she would come back Monday morning, I would guarantee she would be our first patient. She had a multitude of problems, mostly the result of diabetes. We were able to bring her disease under control and now she comes by just to see us and brings five or ten dollars that she donates. I’ve told her ‘You don’t need to do that,’ but she says she wants to, that she’s lived longer than she ever thought she would because of the care we gave her.

“People who can barely speak English take us by the hand and say ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you. I don’t know what my family would do without you.'”

Will he ever completely retire? “I hope not,” McConnell says emphatically. He still has things he wants to do.

“I’d like to see more free clinics. There are about two-hundred-and-fifty-thousand retired physicians–and four times that many retired nurses. Three out of four will come out of retirement if you encourage them.”

If the government would get behind his Volunteers in Medicine model throughout the U.S., McConnell says, “In ten years, we could eliminate the problem of the forty-seven-million Americans without access to healthcare.”

He says helping others is the “food that feeds” him. Reflecting on an enviable career, he says, “I’m just pleased I’ve been able to help someone.”