“There’s no front line in Iraq. Everywhere we stayed was the front line,” said Dr. Joan Sullivan, a member of the National Guard, describing her 2005 tour of duty.

As a surgeon for the 42nd Infantry Division, the 1987 graduate of the UT Health Science Center was deployed to Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s hometown. The division’s deployment marked the first time a National Guard unit had been sent into combat since the Korean War.

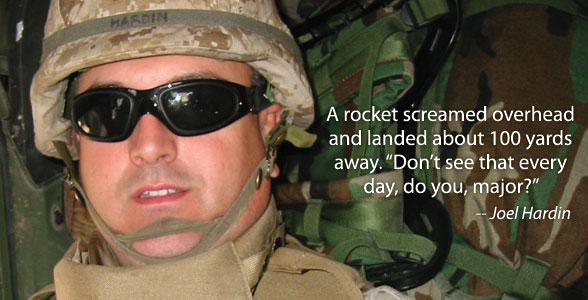

Dr. Joel Hardin’s first day in Iraq reinforced Sullivan’s point. A classmate of Sullivan and a surgeon for 3rd Battalion, 24th Marines, Hardin loaded his gear into a HMMWV (Humvee) ambulance for the final leg of a journey that began in Kuwait and would end a few miles west of Fallujah, in the heart of the Sunni Triangle.

“The Army escort staff from our battalion’s future headquarters rightly asked us to wait a couple of days for the road ahead to be declared clear of roadside bombs–the then-emerging threat to military convoy traffic. So our marines and sailors bided their time,” Hardin recalled. “After two nights of waiting, word came that the route simply could not be verified ‘clear.'” The battalion commander, worried that his troops would be overdue to relieve the Army’s 82nd Airborne Division, decided to push on. “Within five minutes the first roadside bomb detonated, fortunately well off its intended target–no casualties,” Hardin said. The convoy exited onto a two-lane rural road heading toward Fallujah. Minutes later, another roadside bomb targeted a vehicle to their rear. Again, all escaped unharmed, and the convoy moved on.

“We entered a small village and, unlike many villages before, people were not up alongside the road to wave at us,” Hardin recalled. In a deafening blast, the HMMWV ambulance was suddenly rolled over onto its passenger-side wheels. Debris filled the vehicle through a shattered windshield and a gaping tear in the canvas roof.

“We had been the target of a third roadside bomb in a span of just under an hour,” Hardin said. “After a quick inventory, we discovered that all of us–my seasoned chief at the wheel, the Marine lance corporal rifleman next to me, and the Navy corpsman in front of me–were all OK.” Welcome to Iraq.

The two UT Health Science Center College of Medicine grads gave up the better part of a year, smack dab in the middle of their blossoming medical careers, to serve their country. What were they thinking?

“I like the outdoors and athletics so the reserves appealed to me,” Sullivan said. “Before going to medical school, I’d taught at the UT Health Science Center College of Nursing and met some people in the reserves. I wanted an experience that kept me outside on a regular basis.”

Hardin simply had a notion to explore a different aspect of medicine, so he signed up for the reserves. “I really liked all the docs I met who had volunteered for the reserves. There was something different about them.”

Sullivan was a practicing obstetrician, and Hardin, an up-and-coming pediatric cardiologist–not the usual suspects for battlefield duty. As it turned out, their roles went far beyond that of physician. Their primary responsibilities were to ensure that their troops had the best medical treatment possible and were ready to deploy to a hostile environment. And underlying these tasks, the mission was to help the Iraqis regain their lives.

Sullivan advised the division’s commanding general regarding troop medical readiness–immunizations, proper protective equipment, medical threats typical of the region–in the four provinces that made up North Central Iraq. Her role extended to helping Iraqi providers build their own healthcare infrastructure and meeting with the Iraqi surgeon general and the minister of health to guide their efforts. A major challenge was that it was risky for any Iraqi to associate with the Americans: terrorists kidnapped three of the Iraqi physicians who worked with her.

When Sullivan’s team held the first Iraqi-American continuing medical education program, they couldn’t advertise the classes. Instead they spread the information by word of mouth because they knew the terrorists would try to stop them. “We wanted the Iraqis to have confidence in their own medical system, but the terrorists did not want the Iraqis to succeed,” she said. “We were told by the Iraqi doctors that before the war, Saddam Hussein had not allowed any continuing education,” so the Iraqi physicians were behind in the newer medical technology, procedures, and treatments. “Our job was to help them regain their edge in spite of the lack of modern technology, technology we take for granted in the U.S.,” Sullivan said.

As a battalion surgeon, Hardin and the battalion’s corpsmen often dealt directly with the Iraqi people, making medical assessments and delivering basic healthcare to nearby village residents. His team encountered common ailments like high blood pressure and emphysema in the older people, as well as maladies not so commonly seen back home, including significant malnutrition affecting many of the children. In the villages surrounding their camp, the battalion’s command staff met with local sheiks and advised where to rebuild clinics and other critical infrastructure–all with the primary goal of building trust.

At night both doctors returned to quarters that were quite nice by wartime standards. Sullivan usually stayed in “fixed facilities,” sometimes old palaces from the Saddam Hussein era. But there was one minor problem: the water in the palaces was contaminated. This meant tons of bottled water for brushing teeth and washing faces. Another housing option was containerized housing units, tiny rectangular trailers. Women showered in the trailers on the odd hours, men on even hours.

In the field, Hardin stayed in a tent with a plywood floor and a makeshift window air conditioner, a blessing in temperatures of 120 to 130 degrees. A cold shower every 3 or 4 days broke through the baked-on sweat. “The compound was guarded twenty-four-seven by way-too-young and, thank God, exceptionally vigilant and tough marines, standing watch under unbelievably difficult conditions and constant threat,” Hardin said.

Though they were in different parts of the country, Sullivan and Hardin shared a common experience. Both were within mortar range of terrorists.

“Early one morning, just at dawn, I was walking to the chow tent for breakfast,” Hardin recalled. A rocket screamed overhead and landed about 100 yards away. “Don’t see that every day, do you, major?” Hardin commented to the battalion intelligence officer accompanying him.

Sullivan recalled a mortar shell landing about 15 yards from her office. “A Navy petty officer was severely injured. The Army medics gave him initial treatment until I got there. He lost both legs, but he lived because he got immediate care.”

In fact, all personnel were trained in basic first-aid skills because no one knew when or where they would be needed. “About fifty percent of our division was trained in combat lifesaver skills,” Sullivan said. “We trained anyone who would stand still–MPs, cooks, interpreters, generals.”

“You know you’re a target out there; you just never know how many times you’re in the cross hairs,” Hardin said.

Despite the danger, Sullivan said she felt very protected. She carried a pistol and was guarded by soldiers with rifles and automatic weapons whenever she was off the base. An advance team secured the hospital before her visits. “It was a privilege to be the doc,” Sullivan said. “I was there to take care of our soldiers, and any one of them would have taken a bullet for me or any other soldier.”

“I saw countless acts of heroism,” Hardin said. “One day, one of our rifle platoons on patrol came under small-arms and mortar attack, and a marine was hit in the head, taking out one of his eyes and rendering him unconscious. The corpsman on that squad ran out from relative cover to blanket the wounded marine’s body with his own. Then several other marines and the platoon commander joined the corpsman, carrying their wounded comrade out of harm’s way and back to the battalion aid station.”

When asked if the media coverage of the war accurately portrays the reality of the Iraq situation, both Sullivan and Hardin said the media presents one fairly narrow aspect and certainly not the full picture. “The media doesn’t show the good things, the relationships we’ve built,” Sullivan said. “We’ve turned over a lot to the Iraqis. The Iraqi army, police force, and medical teams are rarely mentioned.”

“The media can never portray what it feels like when you’re there, the loneliness and anger, the lack of immediate gratification regarding the mission,” Hardin said.

Now back in their “day jobs,” Sullivan as an obstetrician-gynecologist in Ithaca, New York, and Hardin as director of cardiology for Children’s Hospital of New Jersey in Newark, the doctors have time to reflect on their Iraq experience. “For the Iraqis to be successful and to have the lives they deserve, they must overcome the terrorists from other countries,” Sullivan said. “Underlying that are years and years and years of intolerance, as well as bad feelings among the three cultural groups, the Sunnis, Shiites, and Kurds. It’s a complex situation. We can’t easily overcome something that’s been entrenched for hundreds of years.”

Hardin describes Iraqi people as not that much different from us. “They’re eager, independent, and ready to take control,” he said.

“The Iraqis are gracious, kind, and wonderful people,” Sullivan noted. “Most realized we were there to help. The prevailing opinion seemed to be, ‘We want the Americans gone. But not yet.'”

“The unique thing about this war was that the generals were out there getting fired on just as we were,” Hardin said. “The Marine leadership never once let the enlisted folks down. They empower, delegate, and trust their people. I’m proud of them all, and proud of what they are trying to do. Not everything works a hundred percent, but they’re doing the absolute very best they can with what they have.”

“The ingenuity and heroism of the American soldier is unparalleled–the things they did during this deployment were nothing short of phenomenal,” Sullivan said. “The vast majority of our troops are proud to be there and proud to be from the United States.”