Listen to this story

What do emergency medicine and deep-sea diving have in common? Nothing, one might say. Dr. Richard Walker would beg to differ.

For Walker, chair of the Department of Emergency Medicine at UTHSC, both involve staying calm and making life-and-death decisions under extreme conditions.

At 51, Walker is board certified in emergency medicine and in undersea and hyperbaric medicine. He is also an international traveler, a certified dive instructor, an underwater cave diver, an experienced sailor and an instructor in wilderness medicine.

His calm and quiet demeanor belies the scope of his experiences and interests that to most might seem extraordinary. As far as he’s concerned, that is exactly as it should be. Where chaos threatens—in the emergency room, on the ocean floor, in the wild—calm is required.

“In medical school, I liked most rotations but didn’t want to be limited to one specialty,” he says. “I took an emergency medicine rotation, and it was the most familiar work environment to me, where novel problems come up and you have to solve them right now under a time pressure, which I was used to from travel, from sailing and from the diving world, where you either solve your own problems or you were going to die. That acute unpredictable problem solving was the most intellectually stimulating of all the specialties to me.”

Indeed, he says, the running joke about emergency medicine physicians is that they are the type of people who run toward loud noises with sharp objects.

It’s important to be unflappable, especially considering Walker and his emergency-medicine colleagues are the front lines of stabilizing patients with a myriad of critical injuries and conditions before handing them off to specialists for surgery or hospital admission. “Anything that can happen to anyone or that people do to themselves or each other, we ultimately take care of,” he says.

“We actually try and select for people with a specific personality,” he says about his work as emergency medicine chair. “When something goes wrong, the normal human reaction is to move away from danger, but we’re looking for people who are willing to move toward the danger and help others.”

Being a team player also is imperative.

“A wonderful part of our job is getting to interact with and learn from our colleagues in virtually every specialty on a daily basis.”

A 2005 graduate of UT Health Science Center’s College of Medicine, Walker was born and raised in Memphis. His parents, Carol and Richard Walker, owned Walker Holidays Travel, the second-oldest travel agency in the city.

“I started traveling internationally around the age of 3,” he says. “I was working with the agency by 12 or 14, helping to take tours all over the world. It helped me get very comfortable with lots of different cultures and unexpected things and unexpected challenges, and that is a huge plus.”

His father was a merchant marine officer and a master open-ocean captain. He taught his son how to navigate the ocean. “I grew up at sea,” Walker says.

“Dad passed away, but Mom continues to work to this day and travel internationally. Mom’s been to well in excess of 100 countries on six continents,” he says. “I’m coming up to almost 50 countries on five continents. Medicine put a damper in my travel.”

He made his first scuba dive at age 12, got certified at 13, and was an instructor and a dive supervisor by 21.

Walker attended Memphis University School, graduated from Rhodes College in 1996 with a degree in biology, earned a master’s degree in molecular and cell biology from the University of Memphis, and graduated from UTHSC, despite being waitlisted after his first application. He completed the NASA Space Medicine clerkship in the Department of Flight Surgery at Johnson Space Center in Houston, working on medical emergencies encountered during space walks.

He completed a residency in emergency medicine at the University of Alabama, where he served as chief resident, and then trained in undersea medicine through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Diving Medical Course, while completing a fellowship at Duke University in hyperbaric and undersea medicine.

Hyperbaric medicine is the use of high-pressure oxygen to treat various medical conditions. For example, it is used to induce stem cells to grow new small blood vessels in and around diabetic wounds so the body can heal itself. Undersea medicine is the study of human pathology and physiology in higher-than-normal pressure, such as that encountered while underwater diving. More recently, it also includes low-pressure environments experienced by high-altitude climbers, pilots and in spacecraft.

“We work with anyone in high- or low-pressure environments for exploration, scientific, commercial or military reasons to ensure that people are safe and can receive medical care unique to their environment,” he explains.

Following the Duke fellowship, Walker returned to UTHSC, where he worked with fellow UTHSC alumnus Dr. Alan Taylor to establish the first Emergency Medicine Residency program for the College of Medicine in Memphis.

“Our goal was to change the face of emergency medicine in the city because you could go to different ERs, and depending on where you went, medical care was not standardized,” Taylor says. “You could get different treatments for the same kind of thing because people weren’t board certified. We wanted to change that, and, ultimately, we did. We were able to change the whole landscape of emergency medicine-boarded docs in Memphis, and now it’s full of them.”

Walker, as the program director, and Taylor, as the assistant program director, led the installation of residents at UTHSC partners, Methodist University Hospital and later at the Elvis Presley Trauma Center at Regional One Health, one of the busiest Level 1 trauma centers in the United States. The residency program has expanded to Baptist Memorial Health Care, giving UTHSC’s Department of Emergency Medicine the capacity to coordinate mass casualty, disaster and pandemic overflow across major academic hospital systems in the area.

Walker and Taylor have switched roles in the residency program, but Walker does not let his administrative duties as the department chair keep him from working shifts in the emergency rooms at Methodist University Hospital and Regional One Health.

“I still like to keep my skills sharp,” he says. “It’s a skill set, and if you don’t use it, it atrophies.”

Plus, working with the residents remains a fundamental draw.

He describes life in the ER as less an adrenaline rush and more an intellectual challenge.

“You never know what you’re going to walk into,” he says.

That’s also what keeps him interested in hyperbaric medicine, treating a variety of conditions, including carbon monoxide poisoning, gangrene, difficult wounds and infections. Regional One Health is the only facility in Tennessee where patients can be treated in a walk-in multi-place hyperbaric chamber capable of providing critical care.

“The hyperbaric side of it is interesting for me,” Walker explains. “Whether it is trying to get an astronaut into a suit faster to get out on the surface of the moon, whether it is working with the Air Force to change the way they do high-altitude flights, or changing decompression protocols for scientific, technical or Navy divers, whatever it happens to be, you are trying to push that envelope to become more efficient, to become safer, to open up new things to everybody. Those are all real-world challenges.”

Because of his training and experience, Walker served at the forefront of UT Health Science Center’s local response to COVID-19. Early in the pandemic, he established training for the Department of Emergency Medicine and the Division of Critical Care at Methodist University Hospital, ensuring all emergency-medicine residents and critical-care fellows had appropriate personal protective-equipment training.

With his experience with mass casualty care, oxygen delivery systems and designing a response to the 2015 Ebola outbreak, Walker was tapped to serve as the chief executive officer and medical team leader for the alternate-care hospital for COVID-19 patients that was set up in Memphis. The hospital was never used; however, Walker was charged with logistics and planning in case it was needed.

Walker is an instructor for the extreme environments class at Duke. He has worked with the Office of Naval Research and the Air Force on the High Flight Program and has served as a consultant to NASA for the Constellation program, a predecessor to the current Artemis program.

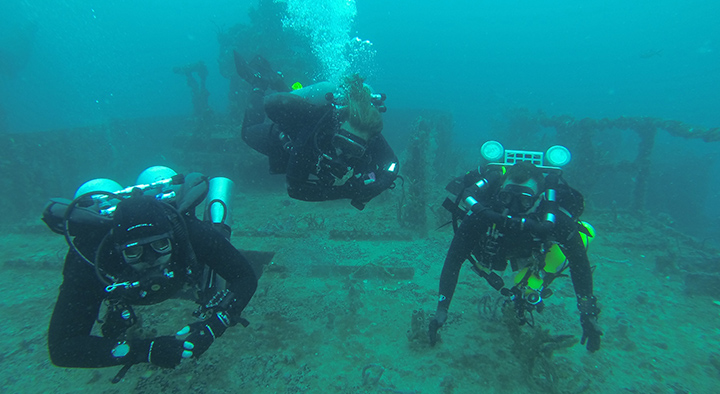

It has been some years since he participated in scientific diving, but he continues to dive recreationally with friends and colleagues.

“Sometimes the dives are cave systems we know well, and other times we dive systems looking for new passages and tunnels,” he says. “It’s one of the few places you can explore on the planet where no one’s ever been before. So we spend our time looking, mapping, always searching for something new.”

“He worries me a little bit,” Taylor says of his intrepid colleague. “I need him around. He’s definitely surprising. He’s always been interested in a lot of things.”

Walker appears unfazed by what could happen during his extreme pursuits. Or perhaps he is just used to running toward danger with sharp objects.

“Only a fool would get into some situations and not be concerned or have caution, but the best way to describe it is that being in the water has always been a part of my life. I have been swimming since I was 6 months old. I was free-diving at age 3½ because there are pictures of me in the Bahamas doing it.

“So it’s 30 years later, and some 4,000 dives and almost 2,000 mixed-gas wreck and cave dives for me, and I have no recollection of a time before I was in the water because I grew up doing it.

“It’s akin to riding your bicycle fast around the neighborhood when you were a kid. It’s still a thrill. You know you could fall, but it’s a familiar environment, and there is always something new to explore.”