For three weeks in June and July, UT Knoxville interior architecture professor Rana Abudayyeh walked with her camera and a notebook through the Zaatari and Azraq refugee camps in her native Jordan, witnessing what she had studied for more than a decade.

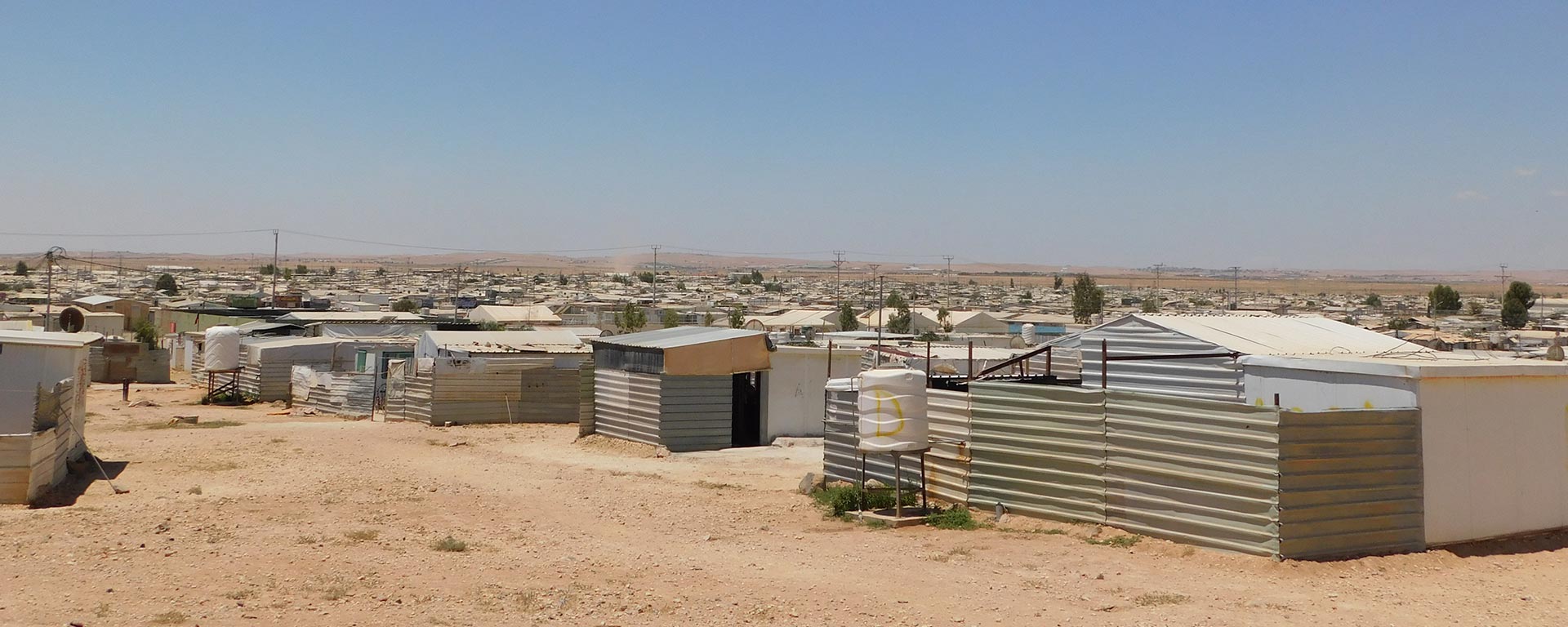

After the Syrian Civil War in 2011 forced more than 14 million people from their homes, approximately 760,000 registered as refugees in Jordan. Throughout the years, Abudayyeh has pored over thousands of satellite images, accounts and other information sources to track how the camps, built as temporary settlements for those escaping from war, were transformed by residents. Where the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and Jordanian government built simple white caravans organized in single files, refugees reorganized the shelters, clustering them beside those of other family members, incorporating courtyards where they could drink tea and talk with neighbors, and planting vegetable gardens to feed their households or sell in the marketplace.

“Refugee communities are resilient,” Abudayyeh says. “They’re inaccurately depicted as a drain on the system, but they are incredibly ingenious societies. Using what they were given in Jordan, they’ve redefined the shelter units to suit their needs and built functioning cities.”

Abudayyeh’s work involves a similar kind of imagination, one that challenges architects to consider the ways people adapt the built environment to suit their needs. The concept, called placemaking, explores how public spaces can be collaboratively reimagined and reinvented to maximize shared value. Placemaking is close to Abudayyeh’s heart, in part because she’s personally experienced the tension. In 1996, Abudayyeh, who is half-Palestinian, immigrated to the United States to attend the University of New Mexico, where she earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in architecture.

Although she is licensed as an architect in Jordan, Abudayyeh joined the faculty of UT Knoxville’s College of Architecture and Design in 2015. She has established herself as a prolific researcher and visionary, earning the prestigious title of Robin Klehr Avia Professor of Interior Architecture and receiving a James Johnson Dudley Faculty Award, which funded her investigation into placemaking and vernacular design in Jordan’s refugee camps.

Most research exploring the design of refugee camps focuses on planning, from building the units to deploying them for immediate use. Abudayyeh focuses on what comes after.

“I’ve always been interested in architecture as a humanitarian practice, as an act of empathy used for understanding and empowering others,” she says.

Before the Syrian refugee crisis, Jordan was already home to one of the world’s largest refugee camps. Al Baqa’a camp, established by the United Nations for Palestinians displaced by the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, grew from tents intended for 26,000 refugees into a city of 131,000, with more than a dozen schools, health centers and a bustling commercial sector. Zaatari, built in 2012 and housing 80,000 Syrian refugees, and Azraq, built two years later with just under 40,000 residents, have charted similar courses.

“The question then becomes, ‘How do we sustain the camps and make sure the people who live there are empowered?’ as camps almost always outlive their temporary status and sprout into areas of long-term settlement,” Abudayyeh says.

This presents a dilemma for the United Nations, the Jordanian government and the international community that has provided resources to the Syrian camps since 2012. Despite their support, the need for long-term utilities, such as water and electricity, is urgent—partly because significant numbers of refugees remain there, even after being allowed to return to Syria.

“While the camps have their challenges, many residents choose to stay when faced with the current conditions in Syria, where their houses no longer exist, and there is no infrastructure, no electricity or schools,” Abudayyeh says. “As many displaced people do, Zaatari’s residents have taken the memory of the place they knew as home into the camps. They’ve tried to recreate what they left in a new environment.”

Before entering the Zaatari and Azraq camps, Abudayyeh passed through several levels of security clearance. Inside, she captured how residents have painted the once-white caravans in colorful hues; splashes of blue, pink and green stand in relief against the harsh desert canvas. Elaborate signs promoting businesses, from clothing stores to fruit stands, line the street; residents rode by her on bicycles, carrying home their purchases.

Many residents gladly welcomed Abudayyeh, showing her how they’d created separate family rooms and bedrooms, hanging rugs and mats as separators. Kitchens were organized using elaborate systems of plastic containers and jars, like in any home in America.

“Big kitchens are very important because families cook together and share meals,” Abudayyeh says. “With refugees, just like any family, sharing a meal is a way of caring for others.”

One middle-aged man had been a concrete specialist in Syria. He showed Abudayyeh where he had poured cement slabs to organize and stabilize the caravan units. As he did so, his wife shared about their daughter’s recent marriage. Even inside the refugee cities, joy rises because, as Abudayyeh experienced, people are still people.

When interviewing families about the caravans’ design, many expressed the benefit of interior storage units or incorporating more fluid partitions. But the more obvious issue to Abudayyeh is that the caravans, which were designed with a seven-year lifespan, are falling apart.

Now home in Knoxville, Abudayyeh is working to create an exhibit of her research, which she expects to have ready in early 2024. She also intends to publish the materials and findings from her trip on an open-source website for others to build on her work. She anticipates returning to the camps and working with refugees, staff and authorities to develop interior-design prototypes for the shelter units to further support and accommodate the long-term needs of families.

“My aspiration is to rethink how we as designers, architects or planners approach sites of emergency need like refugee camps,” Abudayyeh says. “I am invested in finding ways to enable active design engagements in which we all become co-producers of space so that designers, refugees, NGOs (non-governmental organizations), United Nations and other stakeholders all partake in this collaborative working mode where design becomes a platform for empowerment.”