By Peggy Reisser | Photos Courtesy UTHSC (Exceptions Noted)

Jayme Wasson began noticing that her daughter, Lilly, then 18 months old, was losing words and exhibiting behaviors that were a little different.

“Our daughter wasn’t talking, and we really had no way of communicating, which was frustrating for her and frustrating for us,” Wasson says. “It broke our hearts.”

A nurse at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in Memphis, Wasson knew something was wrong, perhaps some kind of speech delay or possibly autism, but for more than a year did not know where to turn for help. When Lilly was 3, a psychologist at work suggested Jayme contact the Boling Center for Developmental Disabilities at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center to get Lilly evaluated. The concerned mom walked the referral papers from Le Bonheur to the nearby UT Health Science Center.

Then everything changed.

Within a couple of months, experts evaluated Lilly, diagnosed her with autism and offered therapies designed to help the little girl and her family.

“What the Boling Center gave us was a new beginning with our daughter, opening lines of communication and teaching us how to help her be her best,” Wasson says.

The Boling Center, now called the UTHSC Center on Developmental Disabilities (CDD), has helped families like the Wassons for more than half a century. With a new name, a new home on the UTHSC Memphis campus and new clinical space on the way, the center remains true to its mission of helping children with developmental disabilities and their families live better lives and training the health-care professionals who will help them do that.

The Beginning

A small diagnostic clinic opened its doors in Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital in 1957. The clinic, which diagnosed children suspected of having a developmental disability, was ahead of its time. In those days, institutionalization, rather than diagnosis and therapy, was often the norm for children with developmental issues.

In the early 1960s, the Kennedy era focused attention and funding toward diagnosing and helping children with developmental disabilities. The federal government funded 19 centers at universities, including UTHSC, across the country to better understand developmental disabilities in childhood.

The CDD traces its roots to that little hospital clinic from the late 1950s; however, its focus is squarely in the present and future. Administered through the UTHSC Department of Pediatrics, its stated mission is to “promote, support and enhance the independence, productivity, integration and inclusion of individuals with disabilities and their families in the community.”

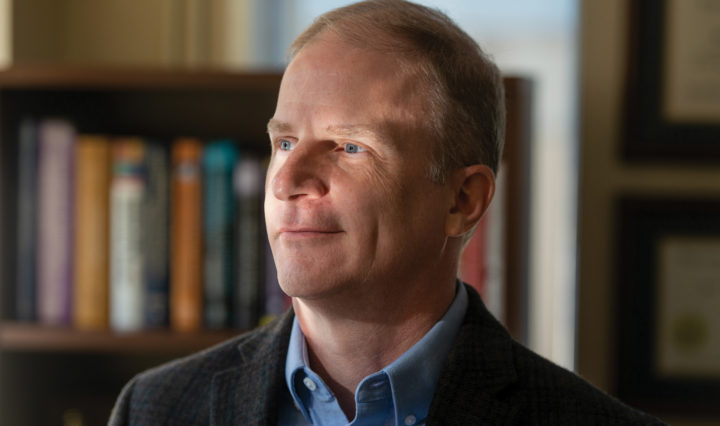

“It’s a real point of pride for us, having been one of the original 19 centers,” says Bruce Keisling, a 2021 Fellow of the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities and UTHSC Center on Developmental Disabilities executive director.

Today, there are more than 125 centers across the United States and U.S. territories. Tennessee has two, one at UTHSC and the other at the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center.

The centers were designed to be interdisciplinary and to study and better understand developmental disabilities. They also were to train the next generation of professionals to care for those with developmental disabilities.

“It really is a two-way bridge that allows the university to inform the community in terms of best practices drawn from research but also lets the community inform academia as to what the current needs are in the states in which we reside,” Keisling says.

Funded today by federal dollars as a University Center for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities and as a Leadership Development in Neurodevelopmental and Related Disabilities training program, it also receives state dollars, medical billing and a few small endowments. The UTHSC Center on Developmental Disabilities includes 11 disciplines, from speech therapy to social work and from psychology to developmental pediatrics. The center provides evaluations, diagnoses and interventions for children under school age, some as early as 18 months old, who are exhibiting developmental issues, such as delayed speech or problems socializing. Referrals come from physicians. Most of the diagnoses and interventions today are related to autism spectrum disorder, Keisling says.

Developing the CDD

A new building was dedicated on the Memphis campus in 1970 to house what was by then known as the Child Development Center. More than a decade later, it was renamed the Boling Center for Developmental Disabilities after Ed Boling, who was retiring as president of the UT System. Through the years, that building, at 711 Jefferson Ave. on the western edge of the Memphis campus, provided a hub of services for children and families.

“At one point in time, it housed a child-care center that was a training venue for us as well. It had the Harwood Center, which was an inclusive preschool for children with and without developmental disabilities. It had the Oral School for the Deaf, which is now in Germantown. It housed a portion of the Memphis City Schools Special Education program up on the sixth floor,” Keisling says. “So there was a lot of intervention being done at different periods of time in the center’s history.”

Belinda Hardy, former associate director of the Boling Center, graduated from the UT College of Social Work in the 1970s and recalls the center from her graduate school days.

“I remember how active it was,” she says. “I remember all of us, residents, speech therapists, social workers, just filling the observation rooms to watch psychologists and therapists at that time diagnose and evaluate children. It was standing room only.”

During those sessions, professionals were introduced to the field of disabilities and could take new skills back to their communities.

“We’re the first entry point for many parents who are trying to sort out what’s going on with their child, whether it’s a speech and language disorder or something else,” Hardy says. “Through the years, it has given them something definitive, and support in that the center sort of breaks down and kind of walks with them through that process of finding out that their child has a disability that’s going to impact their future. So many parents just don’t understand what’s happening, and they need answers.”

Evaluations for children that once took days to complete today are done in one day, says Hardy, who is retired from the center but performs diagnostic evaluations for its Learning Attention and Behavior Clinic.

“So, for example, when we receive a referral, the family or parent is trying to sort out whether or not their child has ADHD, a learning disorder, a reading disorder or what’s going on with this 4-year-old or this 7-year-old that they are not achieving to their maximum potential,” Hardy says. “I will go through a very thorough diagnostic evaluation, share that information with a doctor, and the doctor determines whether or not that child is appropriate for our developmental planning.”

In addition to the diagnostic and therapeutic work, the training mission of the CDD continues to grow, Keisling says.

“Really what we are now at our core is training, research and community collaborations with the stakeholders we work with,” he says.

These include the Center of Excellence for Children in State Custody, which does trainings and evaluations for children with traumatic abuse and maltreatment histories. The CDD also oversees the Shelby County Relative Caregiver Program, which assists families in which relatives (grandparents and others) are caring for children because their parents are unable.

“We’re not a degree-granting center, per se; people come here for the specialty training,” Keisling says. Most often, trainees enroll in the CDD on the path to a degree, as a way to supplement their experience in working with children with developmental disabilities. “They come from a wide variety of places. Some are UT students, but many are from the University of Memphis, and many are from other universities across the United States who come here for a one-year, intensive internship.”

Nemetria Wilson, an assistant professor of psychology at Baptist Health Sciences University in Memphis, received training through the CDD. She’d already earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Howard University, master’s and doctorate degrees in clinical psychology, and completed a one-year internship at a counseling service in Pennsylvania when she enrolled in the UTHSC program to focus on her diagnostic, evaluation and supervisory skills for young clients with developmental disabilities.

“It made me dive deeper into helping individuals with those type of diagnoses, rather than other places I’ve worked,” she says.

Into the Future

In 2021, the Boling Center became the Center on Developmental Disabilities and moved to the 920 Madison Building in the heart of the Memphis campus, putting it closer to where students from other health-care professions study and train.

“We’ve moved from being somewhat off to ourselves on the west side of campus, which meant many people on campus didn’t know what we did or who we serve, to now being in and amongst the heart of campus, and that will pay dividends in terms of new collaborative relationships,” Keisling says.

Eventually, a new diagnostic and therapy clinic will be built on the fifth floor of the building on Madison Avenue, which also houses the Rachel Kay Stephens Therapy Center, a pro bono occupational therapy clinic for pediatric patients that is staffed by UTHSC students and faculty.

“A lot of cross-pollination can occur now that wasn’t occurring because, geographically, we were so far removed from many aspects of campus life,” he says.

Keisling said the center remains committed to its original mission to be “available as a resource to the community and families on all things related to developmental disabilities.”

That certainly was the case for the Wasson family. Lilly, now 5, attends the Harwood Center at the University of Memphis, which offers education for preschool children with developmental disabilities.

“She has excelled,” her mom says. “She’s a happy, happy girl.”

The Nesbit, Mississippi, family continues therapy for Lilly and uses skills at home that they learned at the CDD.

“Had we not gotten in with the Boling Center (now the CDD) when we did, we would have been on a wait list for ABA (applied behavioral analysis) therapy, and that would have taken a very, very long time,” she says. “And these kids don’t have a long time. It’s super important to get that (diagnosis and intervention) really early so they can be prepared and be the best they can be.”