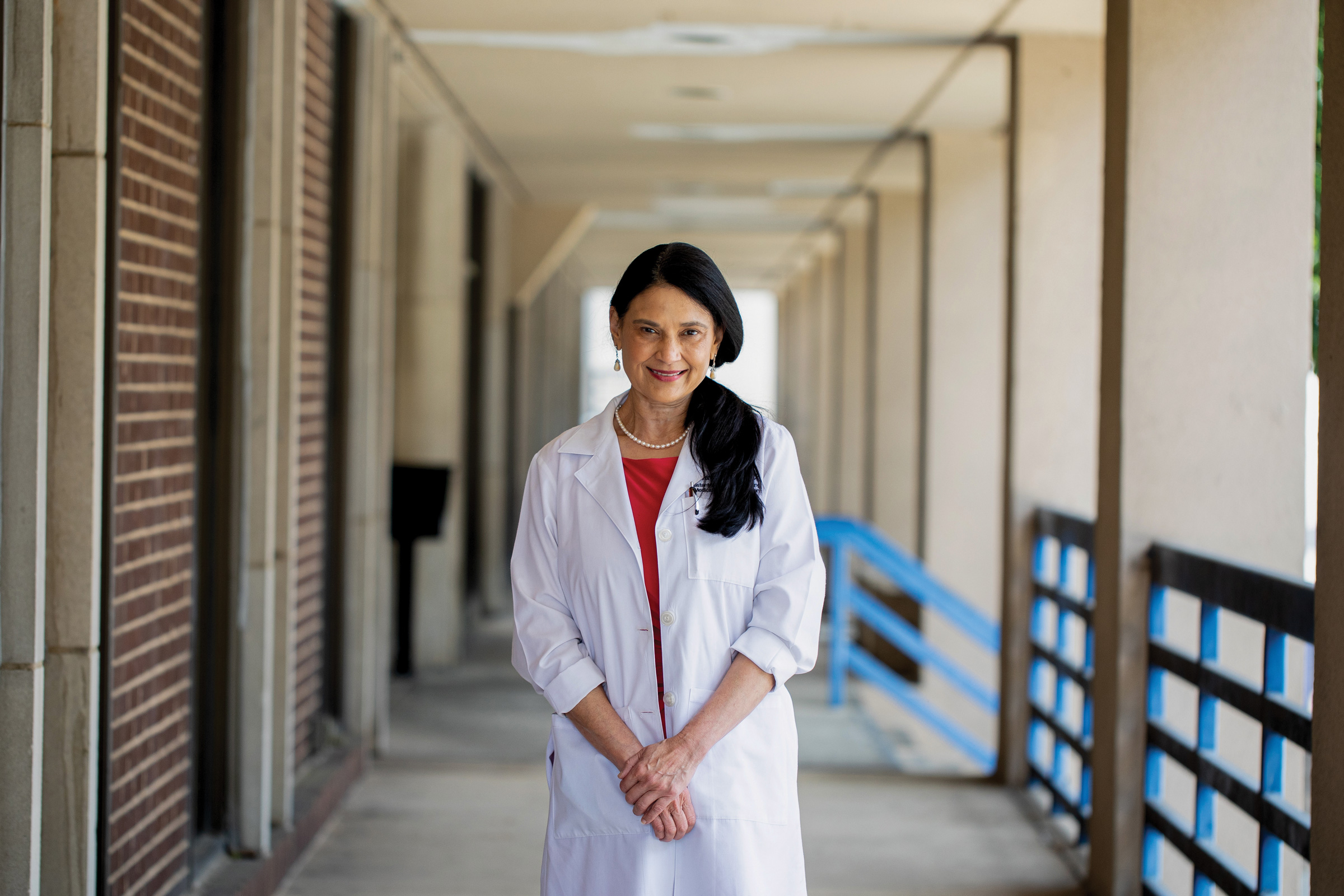

By Peggy Reisser | Photos by Raffe Lazarian

Dr. Mukta Panda still remembers the first dinner party she gave in the early 1990s in Dayton, Tennessee, where she and her family had recently moved. Only a few years in the United States after fleeing the Middle East when the Gulf War broke out, she carefully planned the food, conversation and even what she and her two children would wear: traditional Indian attire for her, American-style clothing for the children.

She had made Indian cuisine. “I had laid everything out on the island, and I was explaining all the dishes,” she says.

Then one of the guests looked out the window, pointing to a shed in the yard, and asked what it was.

“Oh, that’s our outhouse,” she replied. That’s what storage buildings in her native India are called.

“They had these funny looks, and nobody asked for the restroom that night,” she says.

It wasn’t until later she realized her colleagues thought she did not have indoor plumbing.

She can laugh now about the clash of cultures that left her feeling like she didn’t belong. But it is one of the many touchstones that inform her thoughts and actions today as a physician, an educator, a writer, a speaker and a human being focused on living a life of kindness, gratitude and inclusivity, and helping others do the same.

Narratives of Life

Panda is a professor in the UTHSC College of Medicine in Chattanooga, the former chair of the Department of Internal Medicine, and now the assistant dean for well-being and medical student education.

A natural storyteller, she uses narratives, like the dinner party story and so many more, to illustrate and spread a philosophy for living, working and being that she has gained through sometimes uncomfortable life lessons.

“With the world becoming a global village, it is important to really not assume or judge but just to try to understand and humanize our relationships,” she says.

A case in point was her first cardiology rotation as a resident.

Not the primary caregiver on the case, Panda recalls feeling embarrassed as it progressed that she was not doing more.

“All I did was hold her hand,” she says.

Yet that gesture resonated with both patient and physician and endured after the woman recovered.

“I still have the card she made for me with two hands on it,” Panda says.

She believes this scenario illustrates the value of building relationships in health care and elsewhere. This is a central theme of a book she has written through which she aims to humanize health care for those who administer it and those who receive it.

Resilient Threads: Weaving Joy and Meaning into Well-Being was published in January 2020 by Creative Courage Press, just before the coronavirus circled the globe. Its focus on personal reflection and self-care, as well as community awareness and connection, is aimed at health-care professionals but may be applicable, now more than ever, to all.

“I think, especially with the COVID-19 pandemic and the very messy interwoven pandemics of racism and economic crisis that we have faced, it is important to promote a culture that allows us, the authentic self, to show up and not wear a mask,” Panda says.

“I think the whole narrative of equity and inclusion comes from belonging,” she continues. “How can we come from a place of mutual respect for each other? And what we are seeing now, with all the crimes and other things, is our sadness, our hungry cry for belonging. And if each one of us took time for just two or three people to say, ‘Tell me your story. I’m here to listen, that’s all.’ Just taking care of each other. I think we can start with that.”

Lessons from the Past

The daughter of two physicians, Panda was born and grew up in India. She studied and practiced in India, London and Saudi Arabia. A Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians (RCP–London), she came to the United States in 1990.

She and her then-husband, a physician, settled in Dayton because his visa allowed him to work in an area of need. She took a few years off for her small children but realized she missed the long-term relationships and mental detective work of internal medicine and decided to retrain in nearby Chattanooga and complete her residency in internal medicine. She has been there ever since.

She feels her history has shown her the value of relationships, which may get lost in the urgency of health care, the training of those who practice it and the cacophony of everyday living.

“Having been blessed with the opportunity to train in so many different countries and cultures and then having role models growing up, especially in my parents as physicians, that (personal connection) had sort of been the norm,” she says. “When I came to America and was in an educator role myself, I found myself struggling to find the words and the correct ways to really make sure that we were taking care of the whole patient. And, over the past years, in my own experiences as a physician, as an educator and as a leader, both in education and in health care, I have held the tension of how do we humanize medicine. It often feels that we are speaking two different languages.”

In this dissonance, she says, patients and their families can get lost, even though everyone involved wants to do the right thing. At the same time, physicians may feel frustrated and experience burnout from the stress of always caring for others and not taking time to care for themselves.

“So the book is meant to give hope to everybody that, by building relationships, really caring for the person, we may be able to bring the patient back into the center,” she says.

Physicians, too, may find more joy in the connection with their patients and be kinder to themselves in the process. This principle applies beyond the health-care arena.

“When we come from a place of depletion, we’re not effective,” she says. “Self-care is the crucial ingredient for care of others. Then we come from a place of altruism that is not pathologic, but it comes from a place of abundance.”

In Resilient Threads, Panda recounts the story of a well-dressed older woman who came to her for a check-up and continued to schedule appointments regularly every six months for three years, though nothing particularly demanded attention. The personal connection between patient and physician was the draw. When the woman moved away to be near family, she painted a portrait of Panda, which still hangs on the doctor’s wall.

“I never knew she was a painter, but she taught me a lesson—that she connected with me and she had no expectation,” Panda says. “And I was glad for that lesson because now it has even given me more reason to tell people my story and for me to get to know a person better.”

Helping the Next Generation

Panda has dedicated her career to encouraging physicians do that.

In 2009, she helped establish the statewide Gold Humanism Honor Society for the College of Medicine in Chattanooga and serves as adviser to the group, which recognizes medical students who are role models for the human connection in health care. The chapter’s efforts recently were recognized by its parent organization, the Arnold P. Gold Foundation, with its Exemplary Award.

Panda was invited by the UTHSC College of Medicine’s 2020 graduating class to deliver the Hippocratic Oath at its virtual commencement. She is also working to establish another oath as a fixture of medical education to strengthen the physician-patient bond. The Oath to Self-Care and Well-Being, which she co-authored, encourages physicians to care for themselves in order to be able to care for others.

“In framing this oath to supplement our Hippocratic Oath, we see wellness as a shared responsibility between the individual provider and the system, with the major responsibility on the system itself,” says Panda.

One of Panda’s students, Larissa Wolf, a second-year internal medicine resident in Chattanooga, describes her as “a gift and a blessing to everyone she meets.”

Wolf says Panda created a curriculum in conjunction with the Hunter Museum of American Art in Chattanooga that allowed students to go to the museum and reflect on a piece of artwork and do an arts-and-crafts activity to connect art with medicine and their clinical experiences.

“Being in medicine can be extremely daunting, and sometimes we forget that it is an art,” she says. “Those two hours once a month were exactly what I needed to consolidate everything I had learned and seen so far.”

In 2020, Resilient Threads won a Silver Nautilus Award, an international recognition given to books that make a major contribution to inspiring spiritual growth, wellness, responsible leadership and positive social change and social justice.

That year, Panda was named Woman Physician of the Year by the Tennessee Chapter of the American College of Physicians. It’s an honor her student evidently would second.

“Dr. Panda has taught me more than I could ever express,” Wolf says. “She has taught me not only how to be a physician but also how to be a human being.”