By Sarah Knapp

Photos by Nathan Morgan and Steven Mantilla

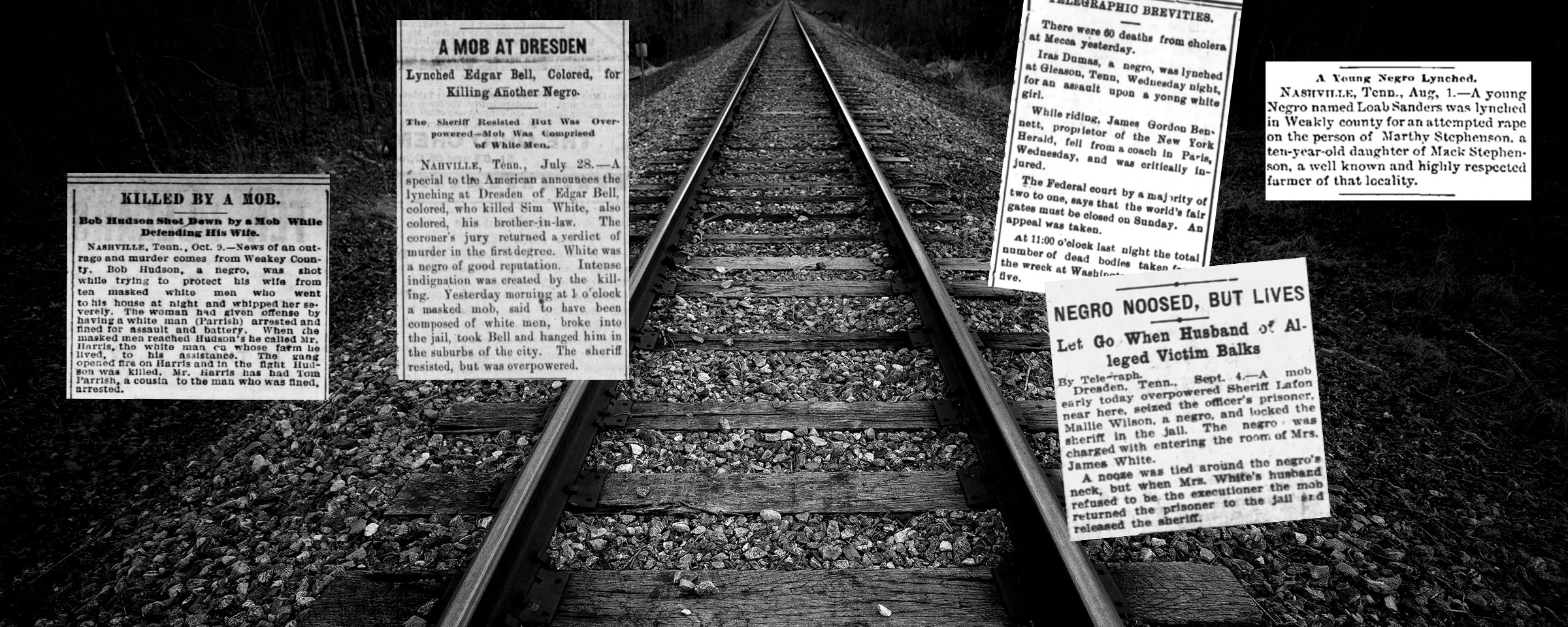

Surrounded by a reported mob of 1,000 and with a noose around his neck for the second time that day, Mallie Wilson knew he would not live to see his 22nd birthday.

The young African American man forced along the Greenfield railroad tracks was condemned for actions for which he had not been found guilty.

The mob accused Wilson of entering the bedroom of Shelia White, a white woman, after dark. Yet she could not identify who came into her room. She “saw it was a negro,” according to the newspaper article at the time. Wilson, who knew Shelia and her husband, James Plummer White, was taken into police custody but was seized by a violent mob on the way to the jail. Members of the mob tied Wilson to a telephone pole with a noose around his neck to await James White to fulfill his duties as executioner. When James White refused to partake in the lynching, Wilson was returned to jail. Later, the mob returned, forcibly removed him from jail and marched him down the railroad tracks to the church he attended on the edge of town.

On Sept. 4, 1915, the eve of his 22nd birthday, Wilson, an innocent man, was hanged and slowly strangled to death while the violent mob jeered and cheered.

“The Dresden Enterprise newspaper article made clear that the purpose of the lynching was racial control,” Carol Acree Cavalier, a Weakley County researcher, says. “The very first paragraph says, ‘The sight of Mallie’s lifeless body was a silent yet impressive warning to the black man that he must keep his place.’”

More than 6,000 race-related lynchings occurred in the United States between the Civil War and World War II, according to research by the Equal Justice Initiative. Even in Weakley County, Tennessee, Wilson’s story is not an isolated incident.

But now the Weakley County Reconciliation Project—a nonpartisan community organization dedicated to facilitating conversations about race, racism and social injustice, in partnership with the Equal Justice Initiative—is working to ensure their names are known.

“There’s no way that we will ever know how many people were actually lynched, but this is a way to honor them. This is a way to put a spotlight on that period of time in our country where this was commonplace,” says Henrietta Giles (Martin, ‘84).

As Giles visited the Equal Justice Initiative’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama, with her family, wandering through the hundreds of steel columns, organized by state and county, dedicated to the victims of lynchings, one specific memorial caught Giles’ attention. She stopped to read on the memorial, “Weakley County, Tennessee: Loab Sanders, July 29, 1892; Lee C. Dumas, June 7, 1893; Edgar Bell, July 27, 1893; Bob Hudson, Oct. 8, 1893; Mallie Wilson, Sept. 4, 1915.”

“Seeing the Weakley County memorial made the issue of lynching more real. The gravity of taking in the memorial as a whole was immense, but seeing the names of people who walked around and lived their lives in the same space where I now live was powerful,” says Giles, a UT Martin communications instructor. “These memorials were a reminder of the horrors that took place in areas that mean a lot to me.”

She wanted to know more about the individuals. But she also wanted to accomplish more.

During her trip to Montgomery, Giles learned the Equal Justice Initiative created each memorial column with a replica designed to be returned to its home county in honor of the victims. To obtain their respective memorials, however, counties must prove they are dedicated to eradicating racial division through community outreach programs.

Through her work with the UT Martin annual Civil Rights Conference, Giles found a group of Martin community members who had also visited the memorial and were trying to create a safe space to further understand what they had learned and experienced at the memorial. Soon after, the small group became the Weakley County Reconciliation Project, and later Giles was elected co-vice president. The Weakley County Reconciliation Project is working with the Equal Justice Initiative to bring the memorial home.

“The purpose of this group is to create a space for people to have conversations about race. That’s the topic that a lot of people shy away from; they just don’t know how to approach it,” Giles says. “We thought it would be a good idea to have a place, create a forum for people to discuss this, to talk about it in a safe place, a safe space. There’s no judgment. There are no harsh responses to people’s experiences because our experiences are our experiences, and we are shaped by those…It’s a way for us to understand each other better.”

Giles says her experiences growing up in Stanton, Tennessee, in the 1960s and seeing her parents’ involvement in the civil rights movement have influenced her as she continues to fight for equality and justice. Giles and her siblings were among the first to integrate the Haywood County schools.

“We were separated in class. There were only a handful of Blacks in each class, and we were not allowed to sit together. We were not allowed to have conversations together. So, it was just very strange,” Giles says.

“I have no memory of playing on the playground because the whole idea was we were not to congregate or integrate with the white children.”

After a bad experience on the bus, Giles’ mother’s words resonated with her.

“She told me, ‘You’re as good as anyone else,’” Giles says. “And I remembered that. That sort of planted that seed in me that I am as good as everyone else, and any opportunities extended to someone else, they should be extended to me as well.”

Now Giles recognizes her parents’ courage to place their children in a situation that wasn’t always safe and admires their dedication to creating a better reality for generations of African Americans to come. She says their willingness to lead the way allowed her to pursue careers unusual for African American women at that time, such as working as a TV writer and producer or teaching at a predominantly white university.

Just as her parents helped to register voters in the civil rights movement, Giles feels her work in the media industry and with the Weakley County Reconciliation Project is her way to continue her parents’ mission to ensure equality for all.

“I feel like that it’s very similar because there is still work to be done when it comes to equality, when it comes to social justice, racial issues. So this is just my way of being involved in something that does deal with racial justice and with creating a better understanding for people,” Giles says.

Though remembering the lynching victims and telling their stories as part of the Weakley County Reconciliation Project has sparked a backlash against the group for “bringing up bad memories,” Giles insists that the purpose is not to place blame but to honor the lives of the victims. Those involved in the lynchings have died.

“So it’s not pointing fingers or trying to shame a community,” Giles said. “It’s a way to say this happened. It was awful, but we are going to remember this person. It’s not making a big political statement; it’s honoring a person. He was someone’s son. He was someone’s brother, friend, relative, and he does not deserve to be forgotten.”

On Sept. 4, 2020, 105 years to the day Wilson died, Weakley County Reconciliation Project members traveled to Greenfield to the location he was lynched and held a solemn commemoration of life in his memory. The group also took turns collecting soil from the area to send to the Equal Justice Initiative Legacy Museum in Montgomery to memorialize where Wilson drew his last breath.

In the process of researching the victims listed on the memorial, Weakley County Reconciliation Project members uncovered three other race-related lynchings through newspaper clippings, including an unidentified boy on Aug. 24, 1869, and William and Edward Johnson on April 24, 1871. As they find more information about each lynching, the group will hold a ceremony for the victims, shining a light on lives lived.

“It’s not a pleasant topic to talk about. I mean, lynching is a very gruesome act, but the fact that this person lived and walked among us, and then they were killed, their life deserves recognition,” Giles says. “Their lives deserve to be honored, where they aren’t forgotten because these are not just isolated people. These are people who had families and other people who are connected to them. This is a way to honor their humanity.”