By Jennifer Sicking

At first glance it seems so small—

.6 percentage points.

“That’s massive,” says Matt Harris, UT Knoxville assistant professor of economics.

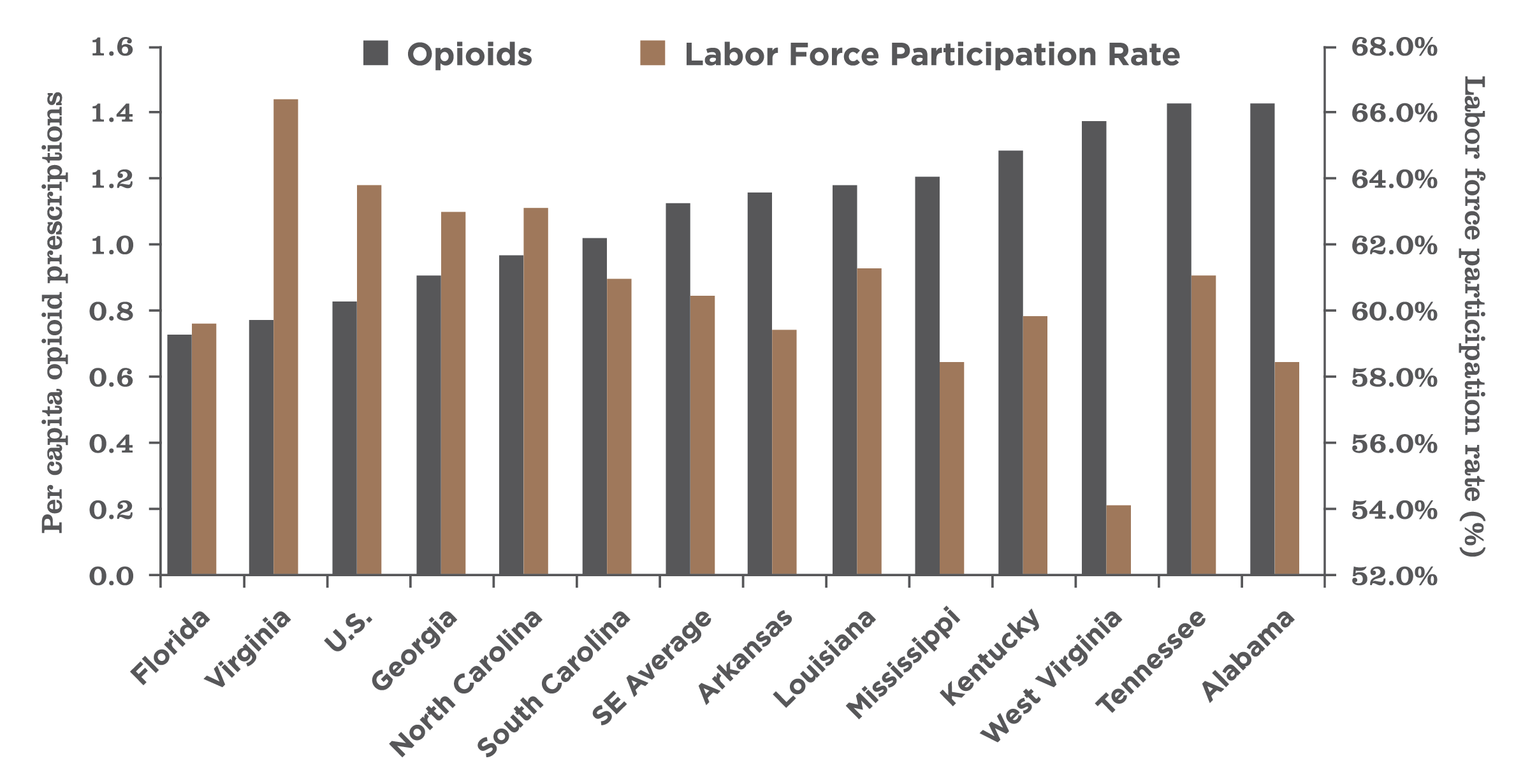

The .6 percent represents the percentage point drop in labor force participation rates when there is a 10 percent increase in prescription opioid rates. That means fewer people are packing a sack lunch and clocking in for eight hours on a job. That small percentage point has millions of repercussions.

And it factors into the opioid epidemic.

Harris along with UT Knoxville-based economists Larry Kessler, Matt Murray and Beth Glenn investigated the effects of opioid use on labor markets. They studied county-level prescriptions of opioids from 10 U.S. states, linked the data to county unemployment, labor force participation rates and employment-to-population ratios and then ran it through advanced statistical methods. Their findings were included as Chapter Four in the 2018 Tennessee Economic Report submitted to Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam in December 2017.

“Therefore, a significant share of the reduction in labor force participation rates since 2000 can be attributed to opioid use,” the economists write in their report.

In January 2018, Haslam responded by unveiling a $30 million plan to begin dealing with the opioid problem in Tennessee.

“This is a crisis that knows no boundaries and impacts many Tennesseans regardless of race, income, gender or age,” says Haslam in the announcement of his plan. The TN Together plan allocates money for prevention, treatment and law enforcement.

In a third of Tennessee counties, a 10 percent reduction in opioid usage would increase labor force participation by more than 1 percent, according to the report. In turn, that would lead to an additional $825 million in personal income across the state. As residents spend money, it would multiply its effect in jobs and taxes for the state.

“Opioids have a big negative effect on labor-force participation, but it doesn’t mean, if you remove opioids from the market, that things will magically get better,” Harris says.

Those addicted to opioids need treatment so they can return to the wholeness of life, including the workforce, Harris says.

“The numbers tell me that, even if you’re completely devoid of compassion for addicts, their families and their communities, this is a battle worth fighting purely on economic terms,” he says. “I don’t mean fighting with heavy-handed restrictions but with careful, evidence-based policies and increased resources for treatment. We don’t have the silver-bullet solution. Our hope is, by shedding light on potential economic gains from successful rehabilitation, that those who can solve the problem will be better empowered and better funded to do so.”

The full report may be found at: http://cber.haslam.utk.edu/erg/erg2018.pdf.