By Erica Jenkins

On Sept. 4, 2013, Tennessee Gov. Bill Haslam issued a challenge with a high bar for higher education: By 2025, take the percentage of Tennesseans with a college degree or certificate from 32 percent—where it sat in 2013—to 55 percent.

The challenge marked the launch of Haslam’s Drive to 55 and its “workforce ready” mission. To attract companies looking to expand and to drive economic growth, a larger proportion of the state’s workforce needed higher levels of education.

Prior to Drive to 55, education entities historically worked toward separate finish lines. High schools drove toward completion. Community colleges tried to increase enrollment. Public colleges and universities competed for state funds based on enrollment and student retention.

Drive to 55’s ambitious goal turned former competitors into teammates as high school counselors, community colleges, and universities scrambled to gear up for the new initiatives and breakneck pace. Once-disparate entities functioned more as a relay team, working together to get every capable student to the finish line: a post-secondary certificate or degre.

Getting students across the finish line required something new and different: flawless relay hand-offs from high school counselors to university or technical school admissions, then from admission to graduation. Ensuring a seamless transition from high school graduate to college student starts by strengthening relationships between universities and high school counselors.

UT Hosts ‘Conferences for Counselors’

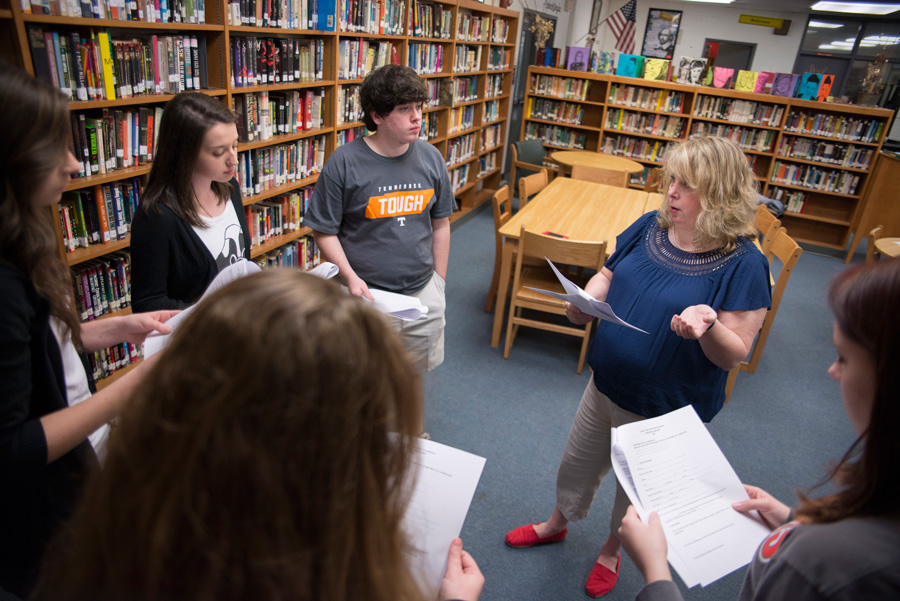

The University of Tennessee System has taken a leadership role in recognizing the importance of high school counselors and reaching out to support them. Staff from the UT System Office of Academic Affairs and Student Success regularly conduct focus group research with Tennessee high school counselors to better understand their needs. The office has used feedback to improve its annual series of statewide conferences each fall that showcase UT’s three unique undergraduate campuses.

Known as UT’s Conferences for Counselors, the series of eight half-day events offered throughout the state give more than 500 high school counselors the latest on admissions and scholarships directly from representatives of the campuses at Knoxville, Chattanooga and Martin.

As a result of focus-group feedback, the 2015 conferences debuted a “UT campus guide.” Counselors had asked for – and they received – side-by-side, quick-reference information on the three UT campuses designed to help them easily navigate a student’s best-fit campus.

For many, high school counselors are partners, walking students through college admissions steps, coaching, managing expectations, giving a dose of reality now and then, and helping each student find the best post-secondary fit. Just as each student’s journey is unique, so is each counselor’s supporting role.

Five counselors from schools across Tennessee provided snapshots of their roles helping students dream, compete and ultimately achieve their higher education goals.

The Guide

Ask Mike Brown about applying for college, and you’ll get a data-driven answer based on 20 years’ experience in private and public school counseling.

At Pope John Paul II, a private Catholic high school in Hendersonville, Tennessee, where Mike serves as director of counseling, most students are from middle-class families and all plan to attend college.

Founded in 2002, Pope John Paul II has become the second-largest college preparatory school in the Nashville area.

Brown’s job is to guide students toward schools where they are best-positioned to succeed. For many of his students, that is UT Knoxville.

“UT Knoxville has always been our No. 1 school – it’s a great value,” Brown says.

An experienced guide is important because of the many factors—financial, academic, geographic and family considerations—involved in college choice. Evaluating those factors for good fit can take time, a luxury typically unavailable to many public school counselors.

“I have less than 200 students in my caseload. Some of my counterparts in the public schools have 300 to 400 kids, and they have more kids who need more services,” Brown says.

While time and caseloads may differ between public and private school counselors, Brown notes that most counselors, public or private, lack formalized training in college counseling.

“I went to Peabody, one of the top colleges for counselor education in the United States,” Brown says of his alma mater within Vanderbilt University, “and I had zero classes that covered anything about assisting kids through the college (selection) process. I was told that I would get that training in my internship. But that ended up being at a zero-tolerance school where I had practically zero kids who were considering higher education.”

Brown paid for most of his early training in college counseling himself, attending summer sessions by professional counseling organizations.

He also developed and co-taught the only graduate course in Tennessee, and one of only 30 in the nation, on college counseling.

According to Brown, Tennessee Promise—which offers community college free to students who graduate high school and complete prescribed steps—has both encouraged access and exposed a gap in training.

“We’re putting a lot of money into, ‘Hey, you can get to college,’ but I don’t know how much we’re putting into, ‘We’ll prepare you to get there,’” Brown says.

“We need more counselors who are better able to address the needs of the kids and help them figure out where they fit and how they can get where they need to be.”

The Coach

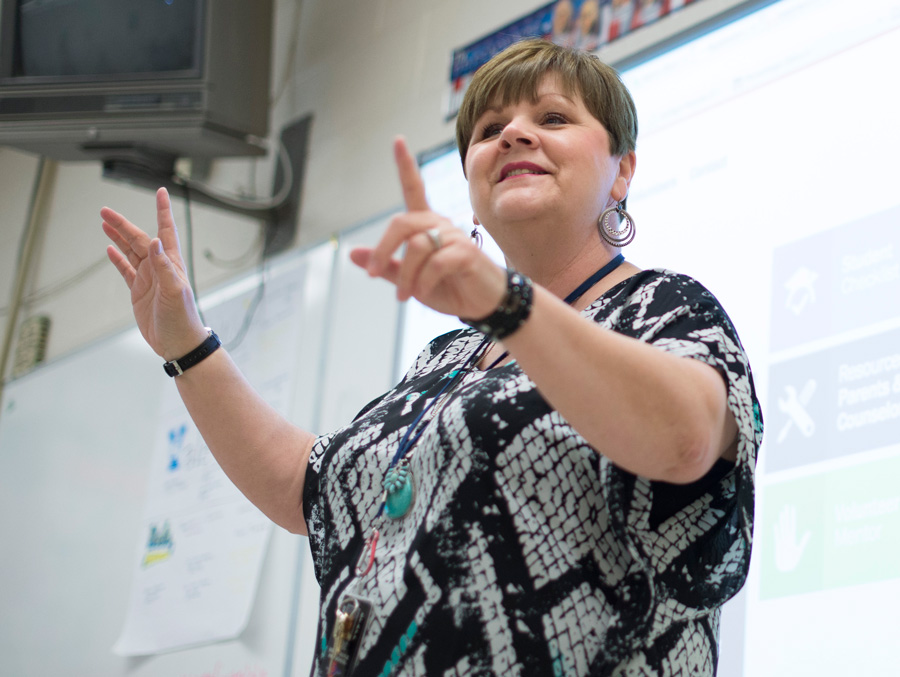

Sonja Wood, the college access coach at South Doyle High School in Knoxville, may have a great sense of humor, but like any coach, she takes her role seriously.

“I feel like I’m aging everyday, but this job and the challenges it brings keep me young—at least in my mind,” she says with a laugh.

In a public school serving a largely blue-collar area where most parents didn’t attend college, Wood’s goal is to get 100 percent of her student body to apply to college. For the past five years, she has worked toward developing a college-going culture.

“We’re planting in their minds that we expect them to do something after high school,” she says.

Like an athletic coach scouting new players, Wood makes it her mission to get to know every senior in the school and uses classroom presentations, social media, and one-on-one meetings to encourage students to apply to college.

“I tell them, ‘You can change your mind later, but we’re going to apply today. And I have a tootsie roll for you when you’re done,’” she says.

Wood’s making progress toward that goal of 100 percent of South Doyle students applying for college, too. Last academic year, all her eligible students applied for Tennessee Promise, the first step for many to higher education.

Still, Wood says, she wishes she had access to data from the colleges and universities students chose—such as UT—to see whether she guided them on the right path. Since most of her students will be first in their families to go to college, Wood often finds herself supplementing the role families usually play in the college selection process, building relationships so students feel empowered but also are held accountable.

“So many are looking for somebody to be an adult and tell them what they need to hear,” she says. “I can look them in the face and say, ‘Look, I’m going to talk to you like your momma, and here’s the deal.’”

She breaks down, step by step, what can be an overwhelming process for students. With her encouragement and guidance, they take the ACT, work with their parents to fill out financial aid paperwork, and then apply for college.

College-focused positions, like Wood’s, are rare in public high schools where many students need extra help pursuing college admission.

“Without this position, the duties would fall to guidance counselors already overwhelmed with class scheduling, testing and crisis counseling,” she says.

The grant funding Wood’s position ends with the current academic year. She hopes that, as part of Drive to 55, positions like hers could be funded long-term to help build a college-going culture in schools statewide.

Video: Five high school counselors describe the college application and selection process in their own words

The Realist

For Heather Waldron, 11th- and 12th-grade counselor at Loudon High School, in the town of Loudon, Tennessee, the key to getting students to dream beyond high school is to focus on reality.

And for most of the 730 students in her rural, public high school, reality is about money.

Sixty-five percent of Waldron’s students receive free or reduced-cost lunch. A majority of the student body would be first-generation college students.

“My kids who struggle academically, they shut down when talking about college. They don’t think that they’re capable or can afford it,” Waldron says.

She explains to them they’ll need more education to achieve a better standard of living.

“If you’re a high school student making $7.50 an hour, and you’re living at home, and your parents are paying your bills, you think you’ve got money,” she says. “But when you start being responsible for more than that, you need more education.”

Waldron credits Tennessee Promise with helping more students – who might not have otherwise – realize college can be a reality.

“For kids who haven’t been academically successful in high school, there’s an awareness that there could be something of interest to them, such as a trade school.”

Once students decide to pursue college, Waldron then must help them confront one of the realities of living in a rural area – lacking Internet access. That becomes an issue as the steps to apply and attend college all are largely online now, from signing up for the ACT to paying a campus housing deposit.

“You’ll ask a kid, ‘Do you have Internet at home?’,” she says. “If they say ‘yes,’ what they mean is they have Internet on their phone, but they may not have data left this month.”

To help students overcome this hurdle, Loudon High provides computer and Internet access. Waldron uses the challenging realities many of her students face to build a foundation for post-high school plans.

“It can be a challenge because, if you don’t feel safe, and you’re hungry, it’s really hard to prioritize the other stuff,” she says. “But sometimes school is a safe place, and school feeds you. That’s a foundation we can work from.”

Although Tennessee Promise is getting many of her students to community college, nearly a quarter of Waldron’s seniors pursue four-year universities. In March, one of her brightest students, Loudon High valedictorian Courtney Wombles, was named a Haslam Scholar. Established by a gift from Jimmy and Dee Halsam, the scholarship grants 15 freshmen admission into the Haslam Honors program, a highly competitive and academically rigorous program at UT Knoxville.

Waldron’s own daughter, Caroline, completes her freshmen year at UT Chattanoga in May.

“She’s been wildly successful as a Moc!” Waldron says.

UT’s Conferences for Counselors, which led Waldron to explore UT Chattanooga with her daughter, is her favorite college event of the year.

“I love having access to three great schools at once and look forward to sharing the information with my kids,” she says. “I also feel the conference helps ‘even the playing field’ for my students,” she says, “because I am able to share the same information that students with dedicated college counselors could get.

The Matchmaker

At St. George’s Independent School in Collierville, Tennessee, college counselor Timothy Gibson helps students through the process of pairing off with the right college.

“Each year, I remind the students they’re not looking for that one perfect school; but they will, in fact, be happy in a lot of different places,” he says.

At St.George’s, helping match with a university starts with students submitting a list of criteria in their junior year. Criteria include financial range, desired distance, school size, and any additional specifics.

From there, Gibson works with students to develop lists of schools to which they will apply. For every “dream school” to which a student applies, he encourages applying to a college at which admission is likely certain.

Sometimes a student’s love of a school is unrequited. When that happens, part of Gibson’s job is helping the student get past the rejection and disappointment.

“I tell them, ‘You have 24 hours. Go eat ice cream, be mad, and take a moment to break up with that school,’” he says. “ ’You will have other options. And you not being able to go to that school is their loss.’ ”

During his time as a counselor, Gibson says, he’s noticed the matching process has become more uncertain as students apply to more colleges and admissions departments use holistic review processes, in which weight given to some criteria can be ambiguous or variable.

“As students are applying to more schools, colleges are trying to figure out who’s really interested,” he says.

While its proponents argue holistic review in college admissions is a way to better assess a student’s total achievements, it can complicate a counselor’s job when the review process is unclear.

“There are some decisions that are really shocking to us,” Gibson says. “Having a more transparent process would help us better advise students.”

UT Knoxville is the only UT campus to use holistic review. After academic credentials, additional critieria for consideration can include—but aren’t limited to—honors or awards, special skills or talents, extracurricular high school activities, the student’s personal statement or letters of recommendation from teachers or counselors.

Despite uncertainty in the process, Gibson’s confident all his students will find a college match.

“Each year, you think, ‘Who knows what’s going to happen?’” he says. “But in the end, you know these students are going to go to great places. They’re going to be successful and happy and thrive because they’re making a choice that’s about fit.”

The Manager

Spend five minutes with Joan Vos (UTC ’95), the college counselor at Chattanooga Christian, a pre-K-12th grade school at the foot of Lookout Mountain, Tennessee, and you’re bound to feel more relaxed and calm.

Her quiet, confident demeanor helps parents and students manage their fears and expectations about applying to college.

“The students are often anxious, and some of them don’t even want to talk about it,” she says. “They have pretty high expectations of what college will be like, and they know they could be disappointed.”

While students are afraid of the process, parents are worried about cost.

“There’s so much out there in the media about student debt. Families are afraid to take on any debt, even a minimal amount.”

In addition to managing fears about cost, Vos also manages expectations about paying for college.

“Parents kind of expect that, somehow, college should be paid for in full because there’s a lot of noise out there about scholarships and students loans. But a college education is an investment,” she says.

With increased awareness of Tennessee Promise, Vos finds herself counseling parents on the importance of choosing a school based on criteria in addition to cost.

“I tell parents, ‘Beware the high cost of saving money,’ ” she says, a phrase borrowed from a counseling colleague. “Many of my students are ready for a four-year college experience and will do well.

“Tennessee Promise is a great deal for the right students, but I don’t want students to be undermatched.”

For her students who pursue Tennessee Promise and start at a community college, Vos also worries about the financial implications of transferring from a two-year community college to a four-year university.

Currently, many institutional scholarships focus on incoming freshmen. To accommodate the increasing transfer population Tennessee Promise is expected to generate, Vos has been in talks with UT Chattanooga about scholarship opportunities for community college transfer students.

“We want to make sure that our students who are pursuing a two-year school and are capable of a four-year school are able to make that transition successfully,” she says.

In addition to being concerned about cost, parents want return on investment.

“I have way more students talking to me about graduate school,” Vos says. “They’ve heard from their parents that you don’t make any money unless you have a graduate degree.”

Vos balances parental pragmatism and student choice by reminding parents of the value in the college experience.

“There’s value in the development as a thinker and a problem-solver that occurs,” she says.